A notorious nuclear accident in 1986 emitted radiation and radioactive material into the environment, resulting in a mass evacuation and, eventually, prohibitions that kept humans from re-settling the area.

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ) covers about 2600 square kilometres around the old plant, does not, however, exist for animals.

Princeton University evolutionary biologist Cara Love has been studying grey wolves in the zone since 2014.

The packs have survived and even thrived in the irradiated environment, prompting speculation as to the effects of the radiation on their bodies.

Using radio collars and blood samples to track the wolves across the years, Love and her fellow researchers found that CEZ-dwelling packs were exposed to more than 11.28 millirem of radiation everyday for their entire lives, over six times the legal safety limit for the average human worker.

The researchers also discovered that the wolves had altered immune systems, comparable to people undergoing radiation treatment for cancer.

Love said she has also identified specific areas of the wolf genome that seemed resilient to increased cancer risk.

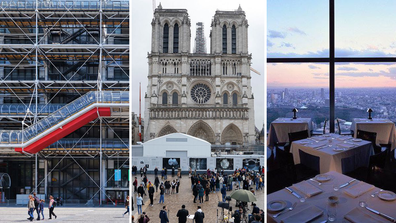

The places you can’t visit in 2024

She hopes to identify protective mutations that increase the odds of surviving cancer.

However, research has been interrupted by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, during which the Chernobyl region became a conflict arena.

“Our priority is for people and collaborators there to be as safe as possible,” Love said.

She presented her research last month at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology in the US.