But there’s another way it impacts the cost of living: shrinkflation.

The term has been popularised in recent years, used to describe when real consumer costs increase despite the retail price of products remaining stable.

What is shrinkflation?

Shrinkflation is a term for when the price of a product remains the same, but the amount of product you receive goes down.

So, for example, if a block of $3 chocolate used to contain 200 grams but is later changed to include just 180 grams, this would be a case of shrinkflation.

How is shrinkflation related to inflation?

Shrinkflation isn’t separate from inflation, it’s actually a specific part of it.

When the Australian Bureau of Statistics calculates the consumer price index (CPI) – the measure used to reflect the rate of inflation – it does so by looking at the cost of what it calls a “fixed basket” of goods and services.

That basket isn’t actually fixed though.

It’s updated in a number of ways, including to account for “quality change” – where the contents of a product change, even if the price doesn’t.

It’s under this quality change umbrella that shrinkflation is reflected in the CPI.

“The use of transactions ‘scanner’ data in the Australian CPI, which provides detailed item information, enables the ABS to identify and adjust for quality change arising from shrinkflation,” the bureau says.

The example it uses is a bottle of drink which costs $3 but falls in volume from 750ml to 675ml.

While the price of the product remains the same, the ABS calculates a price increase of 10 per cent, which is then used in the CPI.

What are some examples of shrinkflation?

Shrinkflation, according to the ABS, is often found in grocery products, so it’s most commonly seen on supermarket shelves.

Read Related Also: Shane Lowry, Justin Thomas brutally mock Bryson DeChambeau over rope mishap

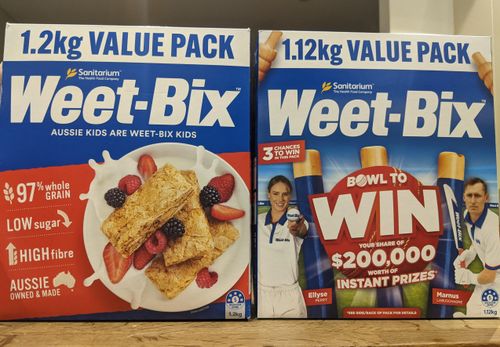

One example of this is value packs of Weet-Bix, which have dropped in weight first from 1.5kg to 1.2kg before going down again to 1.12kg.

Similar shrinks have happened with some other Aussie staples: a block of Cadbury Dairy Milk chocolate used to give you 250g before dropping to 180g; Mars bars have dropped from 53g to 47g; and cans of Pringles now contain 134g of the chips, when they used to fit in 160g.

Why does shrinkflation happen?

Shrinkflation is the result of rising costs for manufacturers; it costs them more to produce the product, and so the amount of product they can sell for the same price decreases.

”It’s hard to get angry at the companies themselves for this, because the price of raw commodities that go into food has been going up with everything else as inflation does,” 9News finance reporter Chris Kohler explained last month.

“Wheat, dairy, cocoa, it’s all been going up, and the companies have a choice: do we jack up the price, or do we make the items smaller?

“Some… have both been getting smaller and been going up in price.”

Does it only apply to groceries?

No. While we typically associate shrinkflation with groceries, it can happen in a range of products.

More broadly, the ABS makes quality change adjustments to about two or three per cent of products in its fixed basket for the CPI each quarter.

Most of those changes actually occur in sectors like clothing and furniture, both of which account for more than four per cent of the adjustments made each quarter, while food products make up just over one per cent.

Who coined the term ‘shrinkflation’?

British economist Pippa Malmgren is widely credited with coming up with the term shrinkflation.

On Twitter in 2015, she wrote she “thought” she was the one who coined it.

“I never learned it, but I use it a lot,” she said.