Every taxpayer in the country will get an unlooked-for cut under a $17 billion promise at the centre of this year’s federal budget, although will have to wait more than a year for it as the government attempts to balance the demand for cost-of-living relief with the need to manage a budget that is now firmly in deficit.

Today’s budget handed down by Treasurer Jim Chalmers shows the national accounts have, for the first time since 2022, fallen into the red.

The $27.6 billion deficit is worse by some $700 million than what was forecast just three months ago in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO), but an improvement on the last budget’s prediction of $28.3 billion.

There’s no prospect of returning to surplus anytime soon, either, with deficits forecast throughout the entire forward estimates: $42.1 billion in 2025-26; $35.7 billion in 2026-27; $37.2 billion in 2027-28; and $36.9 billion in 2028-29.

That figure for the next financial year is actually slightly better than what was forecasted in 2024, although the subsequent years are worse as the government’s main cost-of-living relief contained in this budget – $17 billion in surprise tax cuts for every Australian taxpayer – comes into effect.

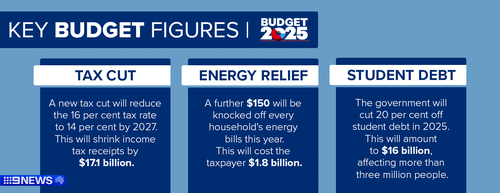

Under the policy, the tax rate for the $18,201-$45,000 income bracket (the first bracket beyond the tax-free threshold) will be reduced from 16 to 15 per cent in 2026-27, and then again to 14 per cent in 2027-28.

That’s a $268 tax cut for 2026-27, and $536 the year after.

“This will take the first tax rate down to its lowest level in more than half a century,” Chalmers said.

“These additional tax cuts are modest but will make a difference.”

There’s also a further $648 million in tax relief through the raising of the low-income thresholds for the Medicare levy.

While Australians have been batting through the cost-of-living crisis, and no doubt would have preferred these new cuts to start in July rather than in 16 months, Treasury is painting a slightly rosier picture for everyone’s hip pockets in the coming years.

Real wages are forecast to have grown by 0.5 per cent by the end of the current financial year – an improvement on what was set out in MYEFO – and GDP growth is set to hit 2.25 per cent in 2025-26, up from this year by a quarter of a percentage point.

At the same time, Treasury expects inflation to remain in the Reserve Bank’s target range for the next three years, bouncing between 2.5 and 3 per cent, while wages rise by up to 3.25 per cent and unemployment caps out at 4.25 per cent – only a small rise from current levels and well below the ten-year average of just over 5 per cent.

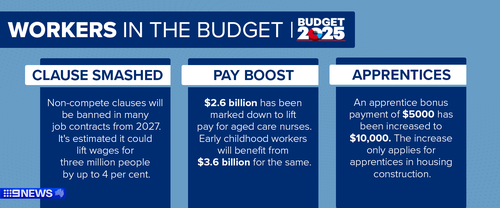

On top of that, the government is promising in the budget to ban non-compete clauses for low- and middle-income workers, a measure it says could boost wages by 4 per cent for those affected, as well as improving productivity – a perennial thorn in the side of the national economy.

“Our economy is turning the corner,” Chalmers said.

“Inflation is down, incomes are rising, unemployment is low, interest rates are coming down, debt is down, and growth is picking up momentum.”

At the same time, the budget acknowledges the current international uncertainty, due in no small part to Donald Trump’s trade war, and the potential for more tariffs on April 2 – a date the US president has labelled “liberation day”.

While Treasury expects the direct impact from tariffs on Australia to be “modest” – the 25 per cent duties on steel and aluminium, for example, are predicted to only knock 0.1 per cent off GDP by 2030 – the indirect blowback could be far more severe.

“A slowdown in global growth stemming from these pressures would also adversely affect demand for key Australian exports, domestic business confidence, and investment,” budget papers state.

“These risks compound the uncertainty in the global economy from conflict in the Middle East and Europe and challenges in the Chinese economy.

“Against this backdrop of greater uncertainty, the global economy is expected (to have)… the longest stretch of below-average growth since the early 1990s.”

There are measures in the budget to combat this – a $20 million boost to encourage shoppers to buy local, and a $3 billion injection for Australian-made green aluminium and iron.

Beyond that, there’s the slew of policies, many of them already unveiled with the federal election looming.

Pay rises for aged care nurses and childcare workers

Both aged care nurses and childcare workers will get boosts to their pay under the budget.

The government will invest $2.6 billion to increase aged care nurse pay, effective from March 1, on the back of a Fair Work Commission decision, while there’s $3.6 billion to increase childcare award rates by 10 per cent from December last year, plus an extra 5 per cent this year.

An extension of the last budget’s headline cost-of-living relief, every Australian household will get $150 in energy bill rebates in the second half of this year, at a cost of $1.8 billion to taxpayers.

Another measure announced in the lead-up to the budget, four out of every five medicines listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme will have their cost slashed from $31.60 to $25, saving Australians $200 million a year.

Medicare bulk-billing boost

While there’s a new $1.8 billion in public hospital funding in the budget, there’s also the government’s February announcement of a $8.5 billion boost for Medicare that will significantly expand bulk billing, making nine out of every 10 GP visits free by 2030.

Three days of childcare for everyone

As announced in late 2024, all Australian families with a combined income of less than $530,000 a year will get access to three days a week of subsidised childcare, at a cost to the budget of $426.6 million.

Also unveiled late last year was a one-off cash boost for anyone with outstanding student debt – roughly three million Australians – in the form of a 20 per cent discount, to be applied on June 1.

This will wipe a collective $16 billion of debt from former and current students’ accounts.