But it also brings a wider issue into focus: Australia’s unabating appetite for single-use plastics, which appears to have only grown in recent years in spite of a wave of new laws clamping down on their use.

In fact, the demand is apparently now so great that established recycling initiatives can no longer keep up.

The Australian government has called on supermarket giants Coles and Woolworths to come up with an alternative soft plastics recycling scheme.

But environmental scientist and conservationist Dr Paul Harvey says a much bigger shift is needed, where recycling becomes “the last line of thinking” in tackling plastic waste.

A resource-intensive process, recycling of soft plastics is also complicated by impurities introduced along the way – such as food scraps left inside plastic bags.

“The primary thought process should be: how can I avoid this in the first place?” Harvey told 9news.com.au.

It comes after NSW became the last Australian jurisdiction to ban single-use shopping bags on June 1, four years after supermarket giants Coles and Woolworths voluntarily phased out their use nationwide.

Yet Australia’s total plastic consumption remains shockingly high.

This is several kilograms ahead of the next offender – the US – and almost four times the global average.

Recent initiatives by governments and retailers such as single-use bag bans have yet to see any measurable impact on these figures.

According to the National Plastics Plan released by the Australian government just last year, Australians get through 70 billion pieces of soft, “scrunchable” plastics such as plastic bags and food wrappers annually.

That equates to roughly 2700 soft plastic items per person.

Despite the growing popularity of recycling schemes such as that run by REDcycle, in 2020 just 12 per cent of Australia’s overall plastic waste was recycled.

The bulk was sent to landfill, where it can take up to 1000 years to decompose, leaching potentially toxic substances into the soil and water.

A further 130,000 tonnes leaches into waterways every year – equivalent in weight to around 130 cargo ships.

The effects on sea life are devastating.

So just where did we go so wrong?

The first wave of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 brought with it a suspension of many reuse and recycling initiatives amid lockdowns and heightened fears around surface contamination.

Cafes stopped accepting reusable coffee cups, Woolworths ended its “crate to bench” service which avoided the need for shopping bags in home deliveries and many loose fresh produce items disappeared from supermarket shelves, replaced with plastic-wrapped alternatives.

While new research has demonstrated that COVID-19 infection via surface contact remains extremely rare, it’s a trend that has been slow to turn around.

So have government bans on single-use plastic bags and other single-use plastics actually achieved their desired intent?

Harvey says the benefits of a plastic bag ban remain “questionable”, as long as their heavyweight plastic alternatives remain permitted.

Read Related Also: Precisely how Nigerian Musician, Burna Son Shutdown His Music Live concert With His Electrifying Performance

Yet these bags closely resemble their lightweight counterparts and are handed out for free at many retailers and takeaway stores.

“It’s a bit of green-washing in a sense – this notion of changing from lightweight to heavyweight plastic bags,” Harvey said.

He notes that, bag for bag, the heavyweight bags are actually considerably worse for the environment.

“They are heavier, they’re thicker so there’s more material,” he said.

“They’re still made from fossil fuel-derived materials to make the polymer.

“And the thicker the product, the longer it lasts.”

Previously among the largest producers of single-use plastic bags, Woolworths and Coles say their bag bans have taken 3 billion and 1.6 billion plastic bags out of circulation annually since they were introduced in 2018.

But these figures fail to take into account new plastic waste introduced in the form of heavyweight plastic bags on sale for 15 cents.

Woolworths says it puts 9000 tonnes of these bags into circulation annually – offsetting a substantial proportion of the estimated 15,000 to 18,000 tonnes its single-use plastic bags weighed.

“Our reusable plastic bags were introduced to help customers adjust to the removal of single-use plastic bags from our stores,” a Woolworths spokesperson said.

Coles has so far declined to announce any similar plans, instead focusing on a trial removal of single-use fresh produce bags currently underway in its ACT stores, which it says will save 11 tonnes of plastic going to landfill each year.

Yet despite moves by major retailers, state governments remain reticent to back these up with stricter legislative measures.

But Australia’s two largest states, NSW and Victoria, currently have no plans to do the same.

The NSW Environmental Protection Agency told 9news.com.au that while it was “pleasing” that Woolworths had elected to phase out heavyweight bags, it would only “review” any such move in 2024 “to determine whether phasing out is appropriate at that time”.

“The EPA will monitor the success of this action before determining whether a future mandatory phase-out is needed,” a spokesperson said.

Harvey believes the reticence comes down to fears around dampening retail sales, as well as resistance from oil and gas companies who supply the raw materials used in plastics.

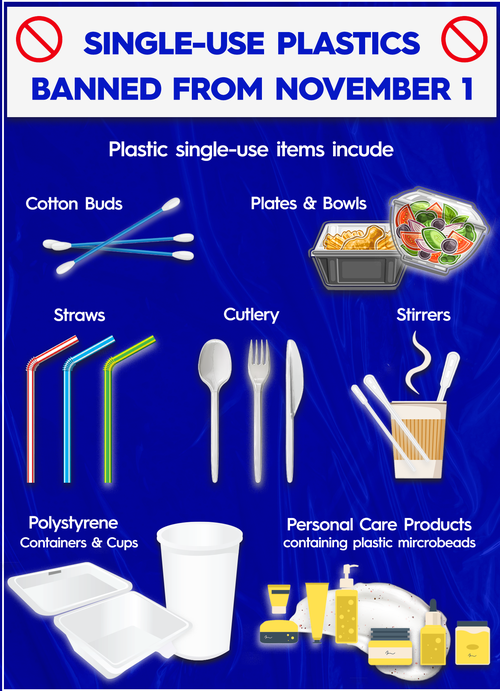

However, Harvey remains optimistic about newer plastics legislation targeting items like microbeads and polystrene containers.

“With the majority of the single-use plastics now being banned, there are currently no other single-use plastics on the market that can take their place,” he notes.

“So fast food outlets will have to switch to cardboard or bamboo products.”

With the future of soft plastic recycling in Australia now so uncertain, the true extent of our single-use plastic consumption will be more evident than ever.