Thousands of them wash up on Australian beaches every summer but scientists have only just discovered that there’s more than one species of bluebottle on the planet.

Until recently the bluebottle or Portuguese man o’ war was believed to be a single species known by the scientific name Physalia physalis.

For decades, scientists operated under the impression that these jellyfish known for their painful sting drifted across oceans all over the world.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprod.static9.net.au%2Ffs%2F8c3d5ef8-155f-479e-b288-30f105de15ac)

Now those beliefs have been utterly debunked.

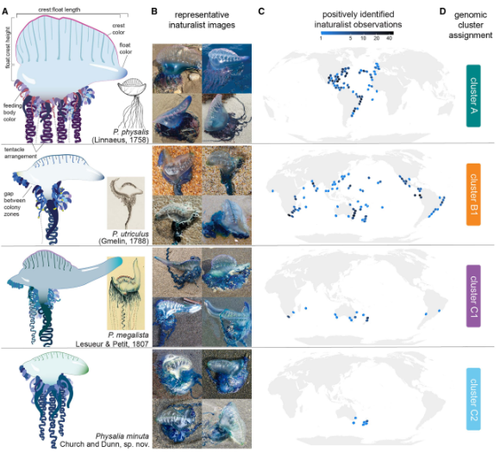

New research from Yale University has proven the existence of at least four distinct species of bluebottle with their own unique appearance, genetics and distribution.

A number of Australian researchers at Griffith University and the University of New South Wales (UNSW) also contributed to the study, including Griffith’s Professor Kylie Pitt, who was shocked by what it uncovered.

“One in six Australians have been stung by a jellyfish and most of those stings are due to bluebottles, and we didn’t even know that we had different species,” she said.

“Here’s a species that causes so many problems along the Australian coast, and we still know so little about it.”

As well as the Physalia physalis, the study proved the existence of the previously proposed Physalia utriculus and Physalia megalista.

It also identified a whole new species called Physalia minuta, which is found in the waters near New Zealand and Australia.

Thankfully, the discovery of additional bluebottle species does not mean there will suddenly be more jellyfish washing up on Australian beaches.

“Your experience at the beach won’t change,” Pitt promised.

Associate Research Scientist at Yale University Samuel Church led the study, enlisting scientists from around the globe to collect bluebottle samples from their local beaches.

Samples from more than 150 animals were sent to Yale, where researchers analysed their genetics.

Everyday Australians also played a part in the project, though they may not have known it.

As well as studying information and samples collected by scientists like Pitt, the Yale research team analysed thousands of citizen-science photos.

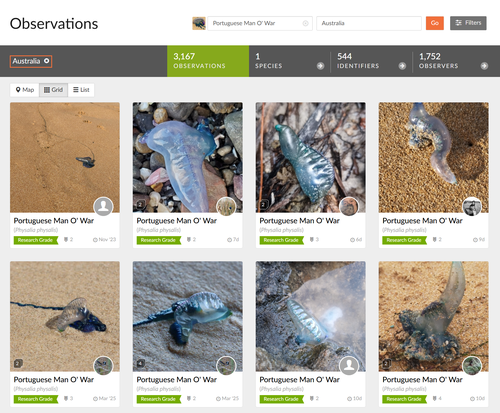

The images were taken from iNaturalist.org, an online social network for nature-lovers where they can upload photos of flora and fauna they’ve seen in the wild.

The website also serves as a “crowdsourced species identification system and organism occurrence recording tool” and was an invaluable resource for the bluebottle study.

There are currently more than 20,000 images of bluebottles on the site, including more than 3000 listed as having been taken in Australia.

“There are hundreds and hundreds of photographs and records of bluebottles from all around the world,” Pitt said.

“So as part of this project, we extracted all the photos and we tried to allocate them to the different species that we identified, based on the way that they look.”

It was a huge undertaking, especially because there was no AI or computer program to help them; every identification had to be made manually.

”Something that people don’t always understand about science is that a lot of it is really repetitive,” Pitt laughed.

And identifying these four distinct species of bluebottles is just the tip of the research iceberg.

This study has opened the door for all manner of research projects in the future, from analysing the biological and ecological differences between species, to predicting when and where each species will turn up on beaches around the globe.

Venom is another point of interest for researchers like Pitt.

“What we don’t know is whether or not some of the species of bluebottles might, for example, have a more potent sting than other species,” Pitt said.

“Are there some that we should be more concerned about than others?”

These are the questions that scientists will be looking to answer off the back of this game-changing research.