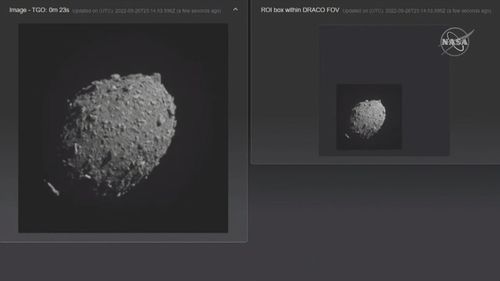

At about 9.15am AEST, the NASA DART rocket made contact with Dimorphos, a moonlet of the larger asteroid Didymos, at about 22,500km/h.

NASA crew monitoring the operation (from Earth, if it needs to be said) cheered as the signal from the rocket was lost at the moment of impact.

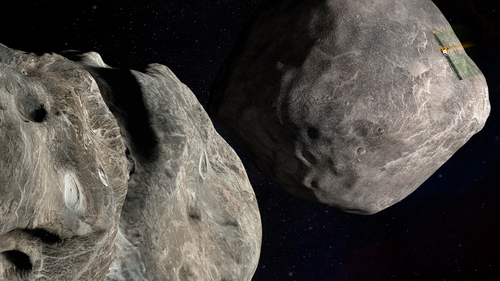

Although Dimorphos is not on a collision course with Earth – and is far too small to pose an extinction-level threat – the DART test is expected to provide invaluable data about altering the course of celestial bodies.

NASA will measure how much the asteroid’s course was altered by, over the coming weeks.

Scientists expected the impact to carve out a crater, hurl streams of rocks and dirt into space and, most importantly, alter the asteroid’s orbit.

The $325 million mission is the first attempt to shift the position of an asteroid or any other natural object in space.

“No, this is not a movie plot,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson tweeted earlier in the day. ”We’ve all seen it on movies like ‘Armageddon,’ but the real-life stakes are high,” he said in a prerecorded video.

Launched last November, the vending machine-size DART– short for Double Asteroid Redirection Test – navigated to its target using new technology developed by Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, the spacecraft builder and mission manager.

A mini satellite followed a few minutes behind to take photos of the impact.

The Italian Cubesat was released from DART two weeks ago.

Scientists insisted DART would not shatter Dimorphos. The spacecraft packed a scant 570 kilograms, compared with the asteroid’s five billion kilograms.

But that should be plenty to shrink its 11-hour, 55-minute orbit around Didymos.

The impact should pare 10 minutes off that, but telescopes will need anywhere from a few days to nearly a month to verify the new orbit.

The anticipated orbital shift of 1 per cent might not sound like much, scientists noted. But they stressed it would amount to a significant change over years.

Planetary defence experts prefer nudging a threatening asteroid or comet out of the way, given enough lead time, rather than blowing it up and creating multiple pieces that could rain down on Earth.

Multiple impactors might be needed for big space rocks or a combination of impactors and so-called gravity tractors, not-yet-invented devices that would use their own gravity to pull an asteroid into a safer orbit.

“The dinosaurs didn’t have a space program to help them know what was coming, but we do,” NASA’s senior climate adviser Katherine Calvin said, referring to the mass extinction 66 million years ago believed to have been caused by a major asteroid impact, volcanic eruptions or both.

The non-profit B612 Foundation, dedicated to protecting Earth from asteroid strikes, has been pushing for impact tests like DART since its founding by astronauts and physicists 20 years ago.

Monday’s dramatic action aside, the world must do a better job of identifying the countless space rocks lurking out there, warned the foundation’s executive director, Ed Lu, a former astronaut.

Significantly less than half of the estimated 25,000 near-Earth objects in the deadly 140-metre range have been discovered, according to NASA.

And fewer than 1 per cent of the millions of smaller asteroids, capable of widespread injuries, are known.

The Vera Rubin Observatory, nearing completion in Chile by the National Science Foundation and US Energy Department, promises to revolutionise the field of asteroid discovery, Lu noted.

Finding and tracking asteroids, “That’s still the name of the game here. That’s the thing that has to happen in order to protect the Earth,” he said.