Exclusive: Dyan Henry, 45, was about to do the school pickup run when an alarm sounded.

It was her continuous glucose monitor (CGM) alerting her that her blood sugar was dangerously low.

Henry lives with insulin-requiring type 2 diabetes but doesn’t show typical hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) symptoms until it’s too late, at which point she can lose coordination or pass out.

If not for her CGM alarm, that afternoon could have turned into a tragedy.

“I was about to get in the car to go to a school with kids everywhere, with the chance that I could have just gone unconscious behind the wheel,” Henry told 9news.com.au.

But she’s had to live without that safeguard for decades because she can’t afford it.

Who gets subsidised CGMs?

CGMs are wearable tech that allow people with diabetes to track their blood sugar levels in real-time without finger-prick tests.

One lasts about 14 days and costs around $100, adding up to more than $2500 per year.

Research has shown that they can dramatically reduce the risk of life-threatening diabetes-related complications for people living with type 2 diabetes.

But under the National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS), CGMs are only subsidised for Australians with type 1 diabetes.

That leaves more than 310,000 people with insulin-requiring type 2 diabetes to pay out of pocket in a cost-of-living crisis or go without.

Henry falls into the second category.

“I work, my husband works, but we can’t even say we’re getting by,” she said.

“We spend every day worrying about, ‘Can we pay our rent? Can we keep our lights on?’

“I can’t pay $200 a month, that’s half a week’s rent. It’s ridiculous.”

As a result, her health has suffered.

Living with type 2 diabetes

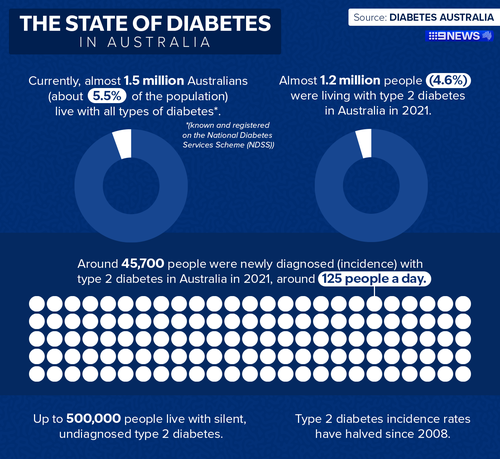

Primarily caused by a combination of genetic predisposition and lifestyle factors, type 2 diabetes affects almost 1.2 million people in Australia.

Individuals with a family history are at higher risk of developing the condition so Henry, whose mother and father both had diabetes, “stood no chance”.

”It was really a matter of when, not if I got diabetes,” she said.

Diagnosed at 23 despite having “no symptoms”, Henry spent years struggling to manage her diabetes with traditional blood glucose meters which require finger-prick tests.

She has autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which made it difficult for her to keep track of her blood sugar and injections.

“Trying to remember to take insulin two, three times a day, checking my blood sugar levels and getting used to needles is hard,” she said.

“A lot of that early time, my diabetes was not controlled at all. It was terrible.”

Henry regularly experienced severe lows without warning because she didn’t experience typical hypoglycaemia symptoms, leaving her confused and barely conscious.

She also suffered multiple devastating pregnancy losses that she said were linked to her uncontrolled diabetes.

‘Life-changing’ wearable tech

In late 2024, Henry was given the chance to trial a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) free of charge and had her life “transformed” almost overnight.

With it, she was able to consistently keep her blood sugar levels within a safe range for the first time in years.

It also woke her in the night when her levels dropped dangerously low, something she previously would have slept through due to a lack of symptoms.

“To have that visual of where [your blood sugar levels] are, where it’s headed, having an alarm with that attached … it was life-changing,” she said.

Henry claimed her health was better in the two weeks she trialled that CGM than it has been in decades.

But without an NDSS subsidy, she can’t afford to pay for them long-term and she fears her health will decline again.

“Sometimes it comes down to: we can afford a monitor, or we can afford the insulin. You can’t fight over that when you really need both.”

Barely getting by, physically and financially

This National Diabetes Week (July 13–19), Henry is calling for the NDSS to change the existing CGM subsidy to include Australians living with insulin-requiring type 2 diabetes.

Many Australians living with type 2 diabetes experience stigma and feel shamed for “bringing the disease upon themselves”.

Henry feels this stigma is part of the reason why people living with type 2 diabetes are not yet eligible for subsidised CGMs.

With so many people already struggling to make ends meet in the cost-of-living crisis, they shouldn’t be made to choose between their health and paying rent.

“I don’t see why it can’t be subsidised for both groups,” Henry said.

“A lot of people who make the decisions have never experienced it, but [CGMs] saved my life and I know they could save so many other lives.”

About one in 15 Australian adults currently lives with diabetes, according to Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data, and the number requiring insulin is expected to rise.

Henry was 33 when she lost her mother, who also suffered from diabetes, and doesn’t want her own child to go through the same thing.

“I don’t want to be hospitalised for a diabetes complication or, heaven forbid, die from one because of something that was unaffordable.”