Over 18 months, the manner and cause of death of unsolved deaths between 1970 and 2010 in the state were examined and analysed as to whether they were gay hate crimes.

There were 22 unsolved deaths examined by the inquiry, which found at least 14 were homicides.

A further six deaths were found to have “objective reason” of being a homicide, while two were not homicides.

“Of those 20 deaths (that either were homicides or there is objectively reason to suspect that they were), all 20 were cases in which there is also, objectively, reason to suspect that LGBTIQ bias was a factor,” Senior Counsel Assisting Peter Gray said.

But the inquiry acknowledged that there is the “unfortunate possibility” that many unsolved cases have been missed as gay hate crimes.

In closing submissions, Gray noted families and loved ones have been struck with grief and devastation for decades.

“In the cases that remain unsolved, there is the additional curse of uncertainty and doubt, a curse which may never go away,” he said.

“For the brothers and sisters of those who have died, the pain can be especially acute.

“When your brother or sister dies, suddenly and unexpectedly and in a violent or unexplained way, something goes hopelessly wrong. The tectonic plates shift and nothing is the same.”

The inquiry raised “disappointing” matters regarding the police investigations of these suspected gay hate crimes over the last 50 years.

It found in some cases documents and exhibits had been destroyed or lost, entire investigative files weren’t produced and uncertainty and ambiguity as to whether investigative steps had been taken or not.

It noted “unsatisfactory and defective” record-keeping by police and a combative attitude.

Read Related Also: Three popular dog foods recalled due to potential Salmonella contamination

The inquiry found for at least several years before it commenced that the police force was aware of these failing practices and failed to inform the special commission of the “underlying systemic problem”.

But well into the inquiry, the police force suddenly produced large swathes of documents the special commission had requested which only extended the process.

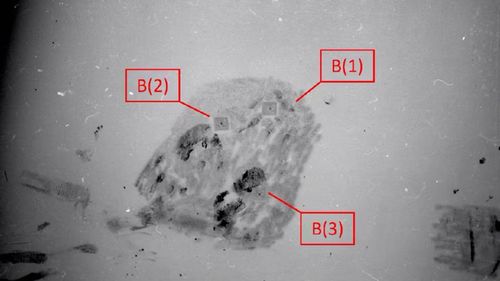

In the case of Ernest Head, who was found dead in his Summer Hill apartment in 1976, the commission re-tested a bloody handprint from the scene of the frenzied stabbing.

Both re-examinations of forensic materials came up with a match, both suspects were men who are now deceased.

The inquiry raised concerns about the failures of the police force to examine the evidence at the time.

The inquiry also condemned the police force’s attitude that sometimes appeared “overly defensive, even adversarial” during proceedings.

John Russell’s body was found at the bottom of a cliff in Tamarama in Sydney’s eastern suburbs in 1989.

For his brother Peter, ire has always been raised at the police investigation into the death.

“I was accused of it. It was the first thing they said to me at Bondi Police Station over 35 years ago, ‘Why did you do it’,” he said.

Despite the bungles raised in the inquiry by the police force over the 50-year period, the inquiry called it an opportunity to right the wrongs of the past moving forward.

“This Special Commission represents a chance for the NSWPF to cooperate with that community in enabling a much fuller picture to emerge of how and why those problems developed, in the ways that they did and to the extent that they did, and in visualising ways in which the future might be different from the past,” Gray said.