But Smith and his team are sceptical. “The eyes of the world are on this impending moral apocalypse,” the inmate and his spiritual adviser, the Rev. Jeff Hood, said midday Thursday in a joint statement. “Our prayer is that people will not turn their heads. We simply cannot normalize the suffocation of each other.”

The US Supreme Court on Wednesday declined to intervene in Smith’s case after his attorneys tried to argue a second execution attempt would violate the US Constitution’s protection against cruel and unusual punishment.

A separate federal appeals court ruling on Wednesday evening also declined to halt the execution. Smith’s team again Thursday morning appealed to the Supreme Court and requested a stay of execution.

State officials on Wednesday welcomed the high court’s rejection of Smith’s earlier request, framing it as an “attempt to bar the state from executing him by any method at all,” Attorney General Steve Marshall said in a statement.

Alabama “remains confident that the execution, and long-awaited justice, will proceed as planned,” he said.

Still, Smith’s advocates and critics of the state fear the nitrogen gas execution could go awry, pointing to its novel nature, questions around its shrouded protocol and Alabama’s recent struggles to carry out lethal injections.

Alabama intends now to try again using nitrogen hypoxia, a method it adopted in 2018. It is one of just three states, along with Oklahoma and Mississippi, that has approved the use of nitrogen for executions, though none has used it and only Alabama has a protocol.

In theory, the method involves replacing the air breathed by an inmate with 100 per cent nitrogen, depriving the body of oxygen. Its proponents contend the process will be painless, citing nitrogen’s role in deadly industrial accidents or suicides.

Others are sceptical, including a group of United Nations experts who this month voiced concern a nitrogen gas execution will “result in a painful and humiliating death,” with no scientific evidence to the contrary.

“It’s lunacy, absolute lunacy,” said Smith’s spiritual adviser, who will be in the execution chamber when the inmate is put to death.

“The process, obviously, is designed to execute Kenneth Smith,” Hood told CNN. “But the way that they’re constructing this, the way that they’re doing it, the way that they’re being silent, the way that they’re holding back information, yes, it’s incredibly concerning. And should be incredibly concerning for everybody in the room.”

Apart from the execution method, Smith’s life should be spared based on the previous, failed attempt to put him to death, said the founder and director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit opposed to excessive criminal punishment that advocates on behalf of death row inmates. The group has assisted Smith’s attorneys in the case.

“Since that time, we’ve been arguing that the state doesn’t have the competency to carry out these executions,” Bryan Stevenson told CNN. “They switched the method, and now they’re saying they have the skill to carry out a method that’s untested and never been used before.”

Smith’s jury voted 11-1 for life sentence

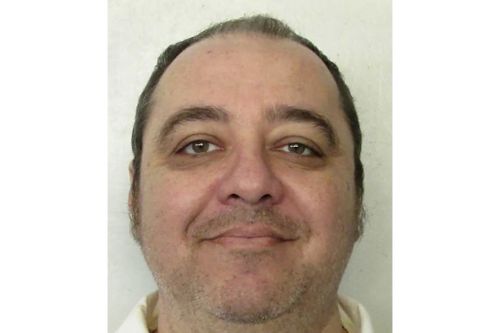

Smith was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of Elizabeth Sennett, whose husband, Charles, was having an affair and had taken out an insurance policy on his wife, according to court records.

Charles Sennett recruited a man who recruited two others, including Smith, and agreed to pay each $US1000 to kill his wife and make it look like she died in a burglary, the records show. The men carried out the killing as planned in March 1988, and Smith took from the Sennett home a VCR player that he stored in his own home.

Charles Sennett killed himself a week after the murder, records state, as the investigation’s focus turned to him. Smith was ultimately arrested after authorities, based on an anonymous tip, searched his home and found the VCR player.

The judge in Smith’s second trial, however, essentially vetoed the jury’s vote and sentenced the defendant to death – a practice known as judicial override that’s since been repealed in Alabama.