Phillip Pembroke never met his father, who he is named after.

He was just a tiny fetus in his mother’s belly on the night his dad vanished 43 years ago.

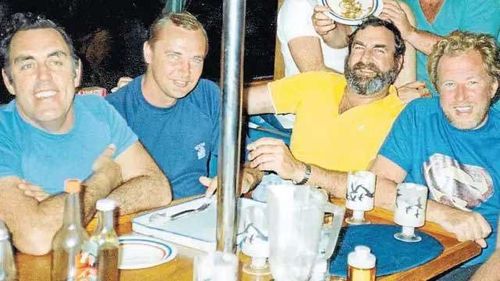

It was August 9, 1981 and Phillip Pembroke senior was flying back to Sydney’s Bankstown Airport from the Whitsundays in a small Cessna plane with three mates and pilot Michael Hutchins.

Somewhere, over the vast and dense Barrington Tops National Park north of Sydney, Hutchins lost control of the plane.

“We’re up and down like a yo-yo,” Hutchins was heard saying in a panicked radio call, before all contact was suddenly cut off.

No trace of the wreckage has ever been found, making it the only aircraft to remain unrecovered on the Australian mainland post World War II.

Pembroke grew up hearing stories about his dad, a former solicitor who became a nursing home proprietor before his death.

“He was a bit of a larrikin. He loved hanging out with his mates and really enjoyed being on the water and around boats,” he said.

“He was just the life of the party and I really wish I’d met him.”

In the days and weeks that followed the crash, large-scale searches involving helicopters and hundreds of volunteers scoured the park’s dense bushland. It was a forbidding task.

There have been many searches for the Cessna VH-MDX since then.

Every year, NSW Police and the SES use searches for the lost plane as a training exercise and the original 80km search zone is gradually expanded.

Amateur aviation sleuths have also conducted their own expeditions in a bid to solve the mystery.

Pembroke himself has taken part in a few of those searches and has been confronted with the difficulties posed by the almost impenetrable bushland firsthand.

“The Lantana and the terrain is like nothing else I’ve seen in my life,” he said.

“You look around and you can’t even see a foot in front of you. It’s just so thick and dense, you could almost walk past the wreckage and not know.”

Avid outdoorsman Darren Taylor, who has made searching for the VH-MDX a dedicated hobby over the years, was on one of those treks with Pembroke, along with New Zealand aviation expert Gavin Grimmer.

Taylor said he was moved by the sight of Pembroke searching for his father so many decades on.

“It’s been a bit of a personal ambition of mine, to help find this plane for the sake of these five families,” Taylor said.

“There’s quite a few of us who are out there, still trying, but we need more help and we need some money to make this thing happen realistically.”

Taylor said different technologies had been developed in the decades since the crash which could be used to help locate the wreckage, including LiDAR imaging.

LiDAR, which stands for light detection and ranging, is a remote sensing technique that measures distances and creates three-dimensional maps of an environment using laser beams.

While LiDAR maps of the Barrington Tops area were already publicly available, more modern equipment could be used to hone in on the forest floor, Taylor said.

“Unfortunately, the area wasn’t LiDAR mapped to look for a plane. It was just LiDAR mapped to get the general topography of the country.”

The petition calls on the government to investigate resources available to the Royal Australian Air Force or the Australian Defence Force which may be able to assist with the search.

Pembroke said he had signed the petition and hoped the government would lend its support.

“With the technology that’s available to us in 2024, I think we could certainly put a more concerted effort into finding these men who left and never came home,” he said.

“I think it deserves another crack, and it would be good to bring them home one day.”

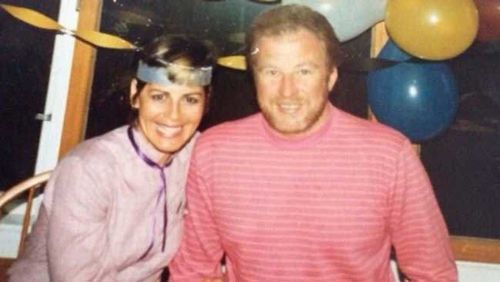

Pembroke said his mother Yvonne, who is now aged in her 70s, never re-partnered or had any more children after the crash.

“She never really got over this incident, because she always clung on to hope that while the plane hasn’t been found, that he’d still be alive.

“She just found it very hard to move on.”

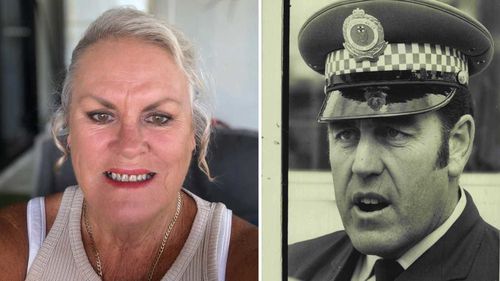

Merrilea Kleins, whose father Ken Price was also on board the Cessna, said the government needed to step in and help “put the mystery to bed”.

“It’s ridiculous. Even with the difficulty of the location, it seems implausible in this day and age that it’s still missing,” Kleins said.

“We can go to the moon, we can go down to the bottom of the ocean to find the Titan but we can’t find a bloody plane in a forest.”

“I don’t think the plane will ever be found unless the federal government steps in.

“Something’s got to change in order for it to happen.”

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau closed their investigation into the VH-MDX more than 40 years ago in September 1983.

The Department of Transport declined to comment on the petition.