When voting in a federal election, citizens vote on two ballots – one for the House of Representatives, the other for the Senate – but the preferential system can seem daunting, particularly for first-time voters.

Here’s everything you need to know about it.

How does Australia’s preferential voting system work?

Preferential voting means voters rank who they most and least prefer to be in parliament.

Australians vote on two ballots in federal elections: one for the House of Representatives (the lower house), and one for the Senate (the upper house).

Preferential voting is used for both, but it works differently for each house.

‘Loves dogs, heavy metal’: Mechanic’s election poster wins hearts

Lower house preferential voting

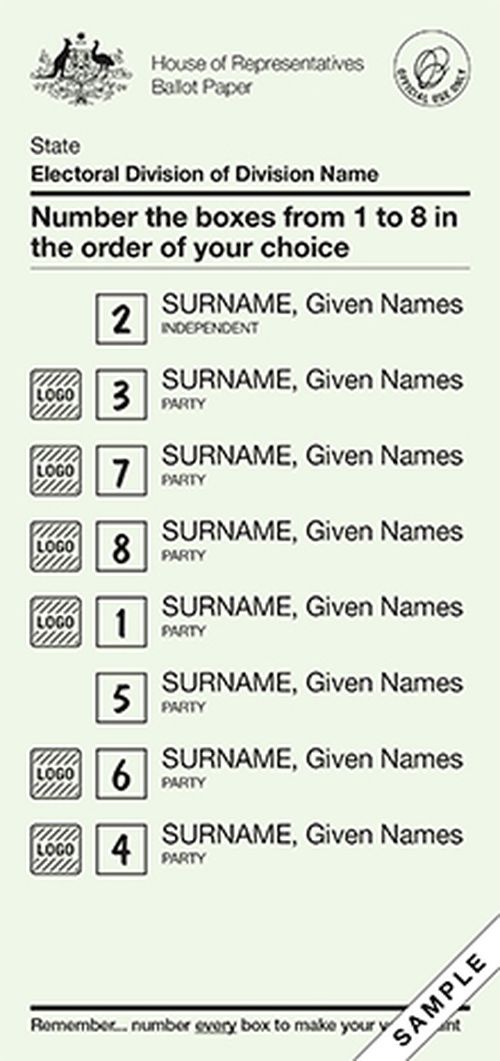

In the House of Representatives, preferential voting ensures a candidate cannot be elected without holding an absolute majority (more than 50 per cent) of the vote – a process that can take several rounds of counting.

This is unlike the “first past the post” system used in the UK, where whoever has the most votes after one count – even if it’s less than a clear, 50 per cent majority – is declared the winner.

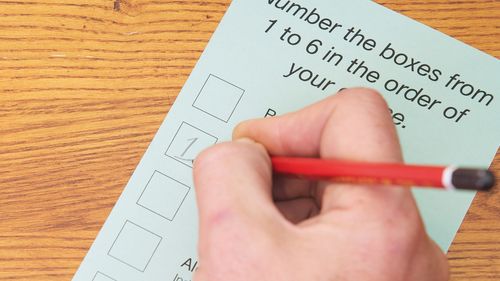

In Australia, voters number all the candidates on their House of Representatives ballot.

Putting a 1 next to a candidate’s name means that is who the voter would most like to represent their seat, a 2 means that candidate is the second choice, and so on until they reach the candidate the voter least wants to represent them.

A vote still counts in full even if its first choice is eliminated.

If a candidate wins the majority of first-preference votes – their name is listed as number 1 on more than 50 per cent of ballots – then they are elected to parliament.

However, if no candidate receives a clear majority during that first count, the candidate with the fewest first-preference votes is eliminated.

Then, in the second round of counting, the eliminated candidate’s votes are transferred to whoever is listed as the second preference on the ballot.

This process is then repeated, with the least-supported candidates being eliminated after each round and votes being transferred until one candidate earns more than 50 per cent of the vote, finishing with a “two-party preferred” result between the two most-supported candidates.

The system means that it’s possible for someone to win a seat even if they don’t get the most first-preference votes.

In the last federal election, Greens MP Stephen Bates won the seat of Brisbane even though he finished third on first preferences, behind the Liberal and Labor candidates.

However, because Labor preferences flowed strongly to him, Bates moved ahead of ALP candidate Madonna Jarrett, and eventually won the majority of votes, beating out Liberal candidate Trevor Evans to claim the seat.

Senate preferential voting

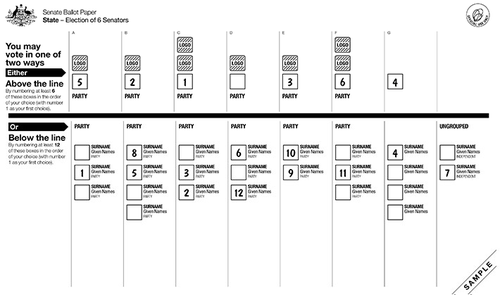

Preferential voting works differently in the Senate, because voters are electing candidates to fill several vacancies for the upper house each election (generally six in each of the states and two in the two territories).

A quota system is used to determine how many votes a candidate needs to be elected. It takes weeks for these results to be finalised.

When filling out their Senate ballot paper, voters can either vote for parties or individual candidates – these choices are known as voting above the line or below.

To vote for parties, voters must number at least six party boxes above the line, with 1 their first choice and 2 their second and so on.

To vote for individual candidates, voters number at least 12 candidates below the line.

When working out who has been elected, the Australian Electoral Commission uses a quota, which is figured out by a formula.

The quota, which is determined by a formula dividing the number of formal votes by the number of vacancies in the Senate, plus one – is the exact number of votes a candidate needs to be elected to the Senate.

If a candidate reaches the quota, they are voted into the upper house.

Any votes for them beyond that exact number are dispersed to the remaining candidates who are marked as second preferences on ballots. These are called surplus votes.

Surplus votes are not counted at their full value. Instead, a formula is applied to determine how much weight they hold – this is called the transfer value.

The transfer value is applied to the remaining candidates’ votes, and anyone who reaches the quota after that process are also elected.

The system continues until all of the available Senate positions are filled.

If all the vacancies haven’t been filled after the surplus votes have been counted, then another process takes place.

The candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their second-preference votes are distributed at full value to the remaining candidates, similar to what happens with the House of Representatives.

Candidates who meet the quota are elected, and the system continues until all the positions are filled.