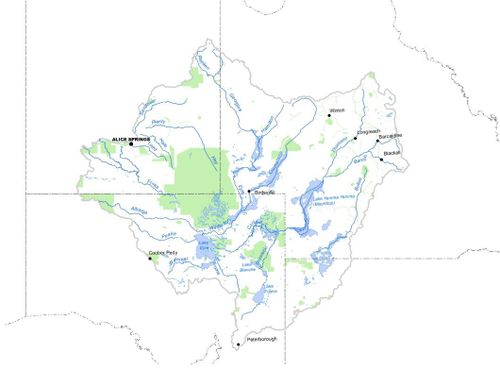

The water will travel thousands of kilometres before it eventually reaches Australia’s lowest natural point, Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre.

The lake hasn’t been completely dry in years, but this amount of water will be enough to fill it – a phenomenon that only happens a few times a century, last occurring in 1999-2001 and before that in the historic flooding of 1974.

In its wake, the water leaves hundreds of thousands of lost cattle and sheep, thousands of kilometres of destroyed fencing and private roads, and ruined machinery.

“The water’s receding, people are getting back into their houses and sheds and seeing this deep, stinking mud that’s covering everything… it’s almost hard to fathom how much destruction there’s been across that vast area,” Dr Jennifer Silcock, an ecologist at the University of Queensland, said.

“Out there at the moment, most people are just really dealing with the aftermath and it’s pretty devastating.

But in this harsh ‘boom and bust’ country, what is destructive will also be regenerative.

Within weeks, bare floodplains will be transformed into lush, green gardens of native grasses, teeming with insects and birdlife.

“It’s just an amazing renewal. What was bare ground becomes this wildflower garden,” Silcock said.

‘Boom and bust’ country

The Channel Country is the last unregulated large river system in the world and the community has fought hard to keep it that way, resisting proposals for irrigation and mining.

“What we’ve got in the Channel Country is so unique and so special,” Silcock said.

“The local residents and the traditional owners and the community and conservationists and ecologists have all worked together to try to keep these rivers as untamed and wild as they can be, because they’re just such an amazing ecological system that we’ve got, and we’re really seeing that expressed at the moment.”

Out there, cycles of deluge and drought are natural and anticipated.

“This flooding is something that these communities and the livestock and the pastoral industry absolutely depend on,” she said.

“That’s why the Channel Country is regarded as being some of the best fattening country for cattle in Australia.

“But I think the speed of it and just the scale of it took people by surprise, the rainfalls were above what was predicted.”

She said as the climate warms, intense rainfall events are likely to become more frequent and less predictable.

“Obviously, we’re dealing with huge amounts of uncertainty because it’s unprecedented what’s happening with the climate, and that’s probably partly why the forecasts are going to start to really struggle to get it right, because what the forecasts are based on is prior events and prior data collected over the last century and a bit more and we’re sort of in uncharted territory now.”

When will the water reach Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre?

Ordinarily, floodwater from north Queensland moves slowly across the landcape, filling the intricate web of tributaries that feed and swell the Diamantina and Georgina rivers and Cooper Creek, sometimes taking months to reach the Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre basin.

Much of it evaporates before it even gets there.

“The water travels very, very slowly because it’s got to fill up a whole network of water holes in the river channels,” Silcock said.

“In some places, the flood plain is more than 50 kilometres wide.”

Once the water reaches the lake there is nowhere further for it to flow and the basin explodes into life.

“When it’s booming, there’s life like you just wouldn’t believe out there… everything’s attracted to that water,” Silcock said.

Seed that has lay dormant in the soil for up to a decade germinates, populations of shrimp, fish, and insects thrive, attracting huge flocks of migratory birds.

But the water is shallow, and evaporates quickly in the intense outback heat, returning the basin to a vast salt pan.

This time, the record-breaking rainfall in March came on the back of five years of above-average rainfall, meaning the muddy torrent of water is travelling south faster than it would if the land was dry and the basin is already wet and green.

“It’s been pretty wet since about 2019, so there would have been some water coming down into Lake Eyre quite a bit over the last five years,” Silcock said.

“But filling Lake Eyre is a totally different thing because it takes so much water to fill it.

“In terms of this amount of water I would imagine it will get fuller than it has been for some years and it could have water in it for a couple of years from now.”

For most Australians, who have never visited the Channel Country, now would be an extraordinary time to see it, she said.

“Once all the roads are open and repaired it’ll be an amazing time to see the floodplains, the big floodplains of the Cooper, the Thompson and the Barcoo as well up further north around Longreach, and then heading down through the Cooper around Windorah and south of Windorah down to Innamincka, all that country’s going to be so green and so full of life.”