At the current rate of greenhouse gas emissions, the chance to limit global warming to the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5 degrees will expire in just seven years.

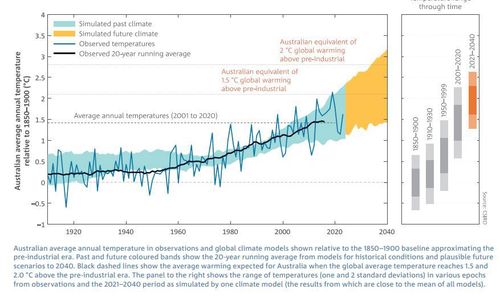

On Australian soil, we are already there, with land temperatures now an average of 1.51 degrees warmer than when records began in 1910.

Within 15 years, an even more dire deadline looms: the chance to limit warming to 1.7 degrees.

Today’s report has laid out exactly how the Earth’s altering climate is already affecting Australia’s weather patterns – from rainfall shifts to extreme heatwaves and bushfires – and what it is likely to mean for our future and our children’s.

Is the 1.5-degree warming target still within reach?

While in absolute terms we still have seven years left, “it’s internationally recognised that it will be very hard to keep temperatures below 1.5 degrees”.

That’s according to the BoM’s National Manager of Climate Services, Dr Karl Braganza, who collaborated on the report.

He said the message to world leaders was very clear: we need to get to net zero as quickly as possible.

However, the reality was harder.

“It’s a little bit like telling someone who has got a large drinking habit or smoking habit, you need to quit that as soon as possible,” Braganza said.

“Obviously, making that change is really hard – it can’t just happen overnight. It involves economic systems, social systems, engineering systems.”

However, global emissions are only just levelling off in the last decade after more than a century of rapid increases.

In 2023, 40.9 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide were released into the atmosphere.

That has brought atmospheric levels of greenhouse gases to a new high of 524 parts per million – over 50 per cent higher than pre-industrial times.

“You have to go back to the Pliocene Epoch – so about three million years ago – to see greenhouse gases at that level,” Braganza said.

Once released, their impacts last for centuries and are extremely difficult to reverse, requiring carbon dioxide removal systems which have so fair proven difficult to produce at scale.

So what does the future hold?

The major changes that the planet has undergone in recent decades are largely irreversible and the next couple of decades of warming are now largely “locked in”, as greenhouse gases already released into the atmosphere continue to heat the oceans.

“But it’s not a case of we’ve gone past 1.5 degrees, let’s give up,” Braganza warned.

“There’s still time to keep temperatures below two degrees… Every bit of mitigation we can do to the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will make a difference later this century.”

The rate of future warming will prove critical in determining just how dire the impacts will be.

“We have Pacific leaders asking us ‘when do we have to leave?'” the CSIRO’s climate research manager Dr Jaclyn Brown said.

“It’s very confronting, very urgent.”

Across Australia, heatwaves are already more frequent and more extreme, bushfire seasons are now an annual event creeping even into the winter months, coastlines are eroding and rainfall patterns have undergone significant shifts.

All of these trends are expecting to intensify this century, but by how much will be determined by how quickly the planet can reach net zero.

Australia has always been known as a land of scorching sun, but if you think the weather is markedly different to when you were growing up a few decades ago, you’d be right.

On average, Australia’s land surface temperature has risen 1.51 degrees between 1910 and 2023, while surrounding sea surface temperatures have warmed 1.08 degrees since 1900.

That might not sound like a dramatic change, but it’s enough to see the number of extreme heat days skyrocket, while extremely cool days become rarer.

In 2019 – Australia’s warmest year on record – there were 33 days when the national daily average temperature exceeded a scorching 39 degrees.

“(In the 1970s and ’80s), you would have to go several decades to record the number of record heat days that we saw in 2019 alone,” Braganza said.

While 2019 was an extreme year, even the comparatively “cool” La Nina years of 2021 and 2022 were warmer than almost any observed during the 20th century.

Since land areas are warming around 40 per cent faster than the oceans, by the time we reach the global 1.5 degrees warming threshold, extreme heat days will be around 3 degrees hotter than they were for most of the 20th century.

“This is not just a little bit hotter,” Brown noted.

“These are long heatwaves, they don’t cool down overnight, our bodies aren’t used to adjusting to that and we don’t have the infrastructure in place.”

Not only will such temperature extremes see heat-related deaths skyrocket, they will impact everything from tourism to agriculture, putting entire industries at risk.

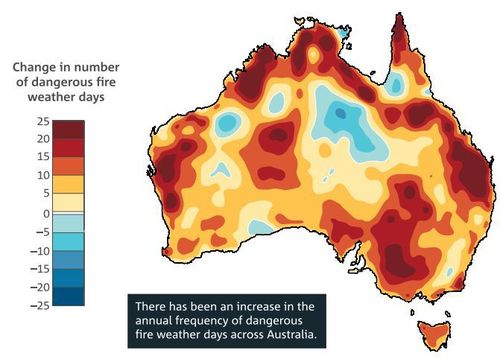

Extreme bushfires ‘the new normal’

“Bushfires are now the normal, and we need to think about those every year,” Brown said.

Not only are more frequent heat extremes increasing the number of dangerous fire weather days, but increasingly rainfall in northern and central Australia is providing abundant grassy fuel.

Conversely, in southern Australia drier winters and springs are creating a parched “tinder box” landscape heading into the warmer months.

While the horror 2019-2020 bushfire season that cost 33 Australians their lives is etched in public memory, 2023 was one of Australia’s most extensive bushfire seasons in terms of area burned, driven by massive fuel loads after years of back-to-back La Niña events.

Parts of southern Australia are also seeing a significant uptick in fire-generated thunderstorms, which can ignite new fires with unpredictable and deadly consequences.

Brown described these findings as “the biggest alarming thing” to come out of today’s report.

Drought to the south, floods in the north

Southern Australia is becoming increasingly drier over the winter months – a trend that has rapidly accelerated in the last two decades.

Nowhere is this more evident than in southern WA, where May to July rainfall has dropped by almost a quarter (24 per cent) since 1994.

Cool season rainfall is particularly critical for agriculture in southern Australia, as it is the main growing season for many crops.

At the same time, northern Australia is becoming wetter, with a 20 per cent increase in rainfall during the wet season, from October through to April.

Because warmer air can hold more water vapour, extreme downpours are also becoming more frequent and more intense even in areas where rainfall is decreasing, with rainfall intensity already up 10 per cent compared to pre-industrial times.

Coastal communities at risk

Globally, sea levels have risen 22cm since 1900, but the worst is yet to come.

In the 20th century, sea levels rose on average 1.5cm per decade; now that rate is closer to 4cm a decade.

Coastal communities and ecosystems will increasingly come under threat, not only as the risk of inundation rises but also from storm surges, erosion and saltwater leaching into groundwater, the State of the Climate 2024 report warns.