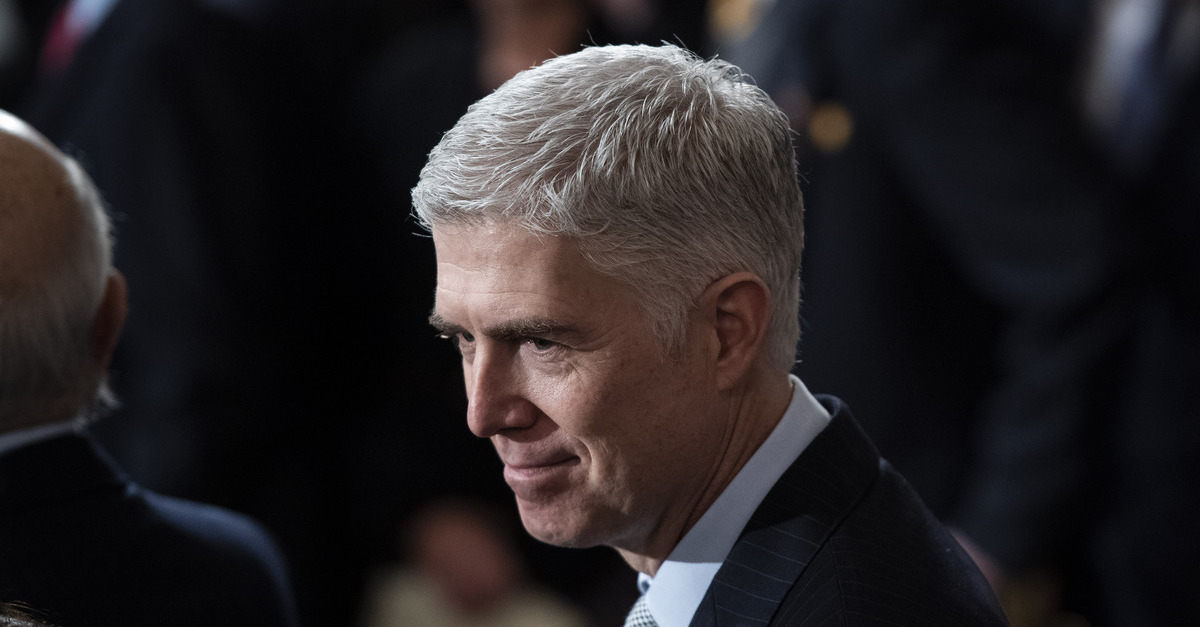

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch appears in a December 3, 2018 file photo (Image by Jabin Botsford/Pool/Getty Images).

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch took Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson to task in a Thursday ruling settling a dispute over whether states can cut Medicaid funding for Planned Parenthood.

In the case stylized as Medina v. Planned Parenthood, the justices issued a 6-3 opinion against the health care provider largely known – and in this case targeted – for its role in providing abortions.

In the case, South Carolina”s decision to cut Planned Parenthood off from Medicaid funds came in accordance with a state law prohibiting the use of public funds for abortion providers. But the underlying law was never in dispute. Rather, Planned Parenthood filed a civil rights lawsuit “to vindicate rights secured by the federal Medicaid statutes.”

Writing for the majority, Gorsuch tears into Jackson – who was joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor – over a litany of different and failed attempts to convince the court.

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

The jurisprudence of the high court has long disfavored the ability of plaintiffs to file lawsuits against the government unless there is a so-called “private right of action,” or a legal mechanism explicitly authorizing litigation in any given statute.

Relevant here, the Medicaid Act does not have such a private right of action – and the parties did not argue such language exists.

Instead, Planned Parenthood tried to use a federal statute, 42 U.S. Code § 1983 – which is a private right of action not entirely unlike, but somewhat short of, a catch-all. The statute is used to vindicate constitutional violations of civil rights. Successful claims under this statute run the gamut from excessive force lawsuits against police to property takings in violation of the Fifth Amendment.

In conjunction with the § 1983 claim, the right the plaintiffs sought to vindicate was Medicaid’s any-qualified-provider provision. This provision says states must ensure “any individual eligible for medical assistance . . . may obtain” such medical services “from any [provider] qualified to perform the service . . . who undertakes to provide” said services — but does not define the term “qualified.”

The majority determined that there is no § 1983 route for such litigation because the Medicaid statute lacks “clear and unambiguous rights-creating language.”

In dissent, Jackson argued the legislative history clearly showed Congress intended for such a litigation vehicle to be created.

Gorsuch, the textualist, tidily dispensed with this argument.

“[T]hat does not move the needle,” the majority opinion reads. “When it comes to interpreting the law, speculation about what Congress may have intended matters far less than what Congress actually enacted. And that goes double for spending power statutes, where ‘the key is not what a majority of the Members of both Houses intend but what the States are clearly told.'”

A secondary argument advanced by Jackson was the idea that Congress intended the Medicaid language in question to mirror part of the Medicare Act which purportedly authorized such lawsuits.

Here, Gorsuch finds two problems.

“This argument stumbles out of the gate,” the majority goes on. “Its premise — that [the Medicare statute] confers an enforceable right — is questionable. As the plaintiffs admit, ‘[n]o court has addressed whether a Medicare beneficiary can enforce this provision under Section 1983.'”

In other words, the dissent argued for a legal theory based on the theoretical application of an entirely-untested parallel legal theory.

But the problem is deeper, Gorsuch says, because the specific area of the Medicare statute uses the word “guarantee” – a word not used in the relevant section of the Medicaid statute.

“So if the comparison between the Medicaid and Medicare provisions reveals anything, it is that Congress did not include in [the Medicaid provision] the language from [the Medicare provision] that the plaintiffs and dissent think most likely to confer enforceable rights.

A tertiary argument essayed by the dissent was to try and tease out a slightly expanded version of a recent precedent created for determining where a private right of action actually exists in a spending power statute.

For years well before the 2022 precedent cited by the majority and dissent, this test existed in the form known as “unambiguous-conferral,” meaning a clear and unassailable right to file a lawsuit.

Here’s how the dissent aimed to frame the unambiguous-conferral test within the facts of the Planned Parenthood case:

Congress also used rights-creating language in the heading of the provision when it enacted the original session law. The provision was entitled: “FREE CHOICE BY INDIVIDUALS ELIGIBLE FOR MEDICAL ASSISTANCE.” This phrasing indisputably invokes language classically associated with establishing rights. And Congress reinforced its rights-creating intent by making the provision mandatory — it specifically inserted the word “must” into the statute — to make clear that the obligation imposed on the States was binding. If Congress did not want to protect Medicaid recipients’ freedom to choose their own providers, it would have likely avoided using a combination of classically compulsory language and explicit individual-centric terminology. As the Fourth Circuit rightly put it, it is “difficult to imagine a clearer or more affirmative directive.”

Gorsuch blasted this understanding.

“Our precedents do not authorize anything like the dissent’s approach — and for good reasons,” the majority continues. “To start, while a title may underscore that the statutory text creates a right, ‘[i]t has long been established that the title of an Act cannot enlarge or confer powers’ by itself. That must be especially so where, as here, Congress chose not to enact into the U. S. Code the very title on which the dissent relies.”

Gorsuch also offers a slippery slope argument. The majority says that if Jackson’s interpretation were to hold, “many other provisions (in Medicaid and elsewhere) previously thought to confer only benefits would suddenly create rights instead.” And that, Gorsuch says, flies in the face of the recent precedent because the court in the earlier case said “only ‘atypical’ statutes confer enforceable rights under § 1983.”

Finally, the dissent argued that without allowing § 1983 lawsuits to enforce the any-qualified-provider provision of Medicaid, states might feel free to ignore the provision. The dissent does note there is recourse for the federal government to punish states who improperly structure their Medicaid programs — by withholding funds. But that method is disfavored and rarely used because it would negatively affect Medicaid beneficiaries.

Gorsuch says the concern here is misplaced.

“[T]his Court has specifically rejected the notion that ‘the cut-off of funding’ is ‘too massive’ a remedy ‘to be a realistic source of relief ‘ for violations of [Medicaid Act] provisions,” the majority continues. “To the contrary, this Court has called funding cutoffs ‘the typical remedy’ when a grant recipient violates the terms of spending-power legislation.”

Gorsuch also notes that, instead of attempting a lawsuit anchored by the statute, Planned Parenthood could pursue administrative relief directly — a claim that could go all the way to the Supreme Court.

“Indeed, Planned Parenthood itself pursued just such an administrative claim at one point,” the majority notes.

As it turns out, Planned Parenthood did try this process, at first — but later missed a deadline to appeal one of the decisions in that case.