I thought Henry Kissinger would never die. Demons have that way about them. They never fade away. They just haunt, like malignant turns of the screw, the way Kissinger screwed on in the half century since he stopped ordering hit jobs on heads of state, mass-murdering civilians and seeding genocide in America’s name.

He tilled the killing fields of Bangladesh, North Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, East Timor and the Middle East and mixed the concrete that holds the disappeared of Chile and Argentina. He made a hero of Ho Chi Minh and a fellow-traveler of Pol Pot. He made Nixon and Brezhnev look like Baptist choir boys.

He tilled the killing fields of Bangladesh, North Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, East Timor and the Middle East and mixed the concrete that holds the disappeared of Chile and Argentina. He made a hero of Ho Chi Minh and a fellow-traveler of Pol Pot. He made Nixon and Brezhnev look like Baptist choir boys.

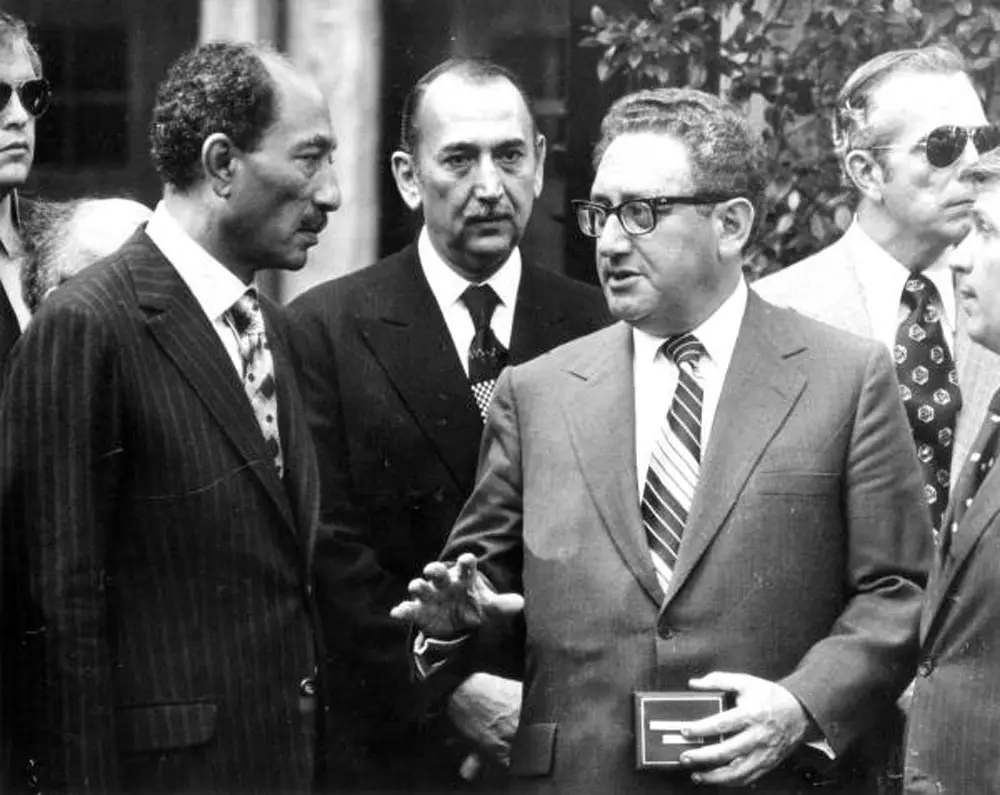

He may have croaked–did he ever not, with that voice of a living corpse?–but don’t be fooled. This is Kissinger’s America. Of the eight presidents who succeeded the Nixon-Ford years only Jimmy Carter, that pansy who had the gall to predicate foreign policy on human rights, had the good sense not to take him into his counsel. (Kissinger had warned Carter not to risk negotiating peace between Egypt’s Anwar Sadat and Israel’s Menahem Begin in 1977 since the outcome was in doubt. Carter told him to take a hike and brokered the Camp David agreement, still the most substantial Mideast peace deal of the last 50 years.)

Every president since, Republican or Democrat, has gone through Kissinger’s re-education camp as if it were the Oracle at Delphi. The oracle dished out bunk. So did Kissinger, who could make a belch sound like a doctoral thesis: above all, don’t lose face. Even Barack Obama fell under the spell, pointlessly stretching the Afghan occupation by eight years to maintain the illusion of American power while that power was hollowing itself out.

What Kissinger called strategy was little more than the amoral vigilantism of a playground bully who happened to have the world’s most powerful military and economy at his disposal. “What interests me,” he had told the journalist Oriana Fallaci in an unguarded moment, “is what you can do with power.”

Means were irrelevant. Only ends mattered. So he railed against press reports from Vietnam and saw the media as the enemy–not because what it was reporting was untrue, but because it was reporting it. There was no reason to keep the Pentagon papers from publication by The New York Times in 1971. It was old history by then. But to Kissinger the secrecy was the point.

In that sense Kissinger was indistinguishable from his Soviet or Chinese foes. He understood and loved their company because they spoke his language: power, secrecy, amorality, prestige. (He once described Hafez el Assad, the Syrian butcher, as “a first-class mind allied to a wicked sense of humor.”) Those who worry about casualties and human rights are naive fools.

After railroading the Johnson administration’s peace overtures to Vietnam during the 1968 campaign, he and Nixon cynically delayed the end of the war by four years to save face, dropping more bombs on Cambodia and Laos than all the bombs dropped in World War II theaters combined. Those bombs are still exploding and claiming lives today. More than a third of American casualties occurred during those “peace with honor” years. The secret carpet-bombing of Cambodia, which achieved no military or political objective, took 150,000 civilian lives and set up Pol Pot’s genocide, which claimed another 2 million, a quarter of the country’s population.

For the past 50 years Israel has inexorably snuffed out Palestinians’ right to exist through apartheid methods of occupation or the strangling of Palestinian enclaves, through settler terrorism against Palestinian natives, and through the massacres of periodic wars of collective and disproportionate punishment against Lebanon, the West Bank and Gaza. This, too, is Kissinger’s legacy: the starting point of any Mideast initiative was biased in favor of an Israeli script, and subject to Israeli vetoes. Israel has wielded that power all along, translating it to impunity. No American president has dared question it. The carpet-bombing of Gaza has Kissinger’s realpolitik blasted all over it, with Biden’s blessing: stand by for his fawning tribute.

“Americans choose strategy over principle every time and yet keep believing in their own innocence,” Don DeLillo wrote in The Names. The line sums up a Kissinger delusion embraced by every president since Eisenhower.

At the heart of the Kissinger delusion is an ironclad disconnect between means and consequences. Kissinger could theorize, talk and wield power all day. What he could not stand was facing the consequences in the field. What he could not stand was the flesh and blood of it all. That, too, was for pansies. That disconnect is frighteningly on display in a conversation in the Oval Office between Kissinger and Nixon as Kissinger applauds the president for deceiving Congress (“no American ground forces are going to be used in Cambodia”) and comparing its members to the enemy in Southeast Asia.

Read Related Also: Sandy Hook families call out Alex Jones for ‘lavish lifestyle’ and ‘massive salary increase’ during bankruptcy, offer a settlement well below a billion

“I want them to hit everything,” Nixon said. “I want them to use the big planes, the small planes, everything they can that will help out here and let’s start giving them a little shock.”

“Absolutely,” Kissinger, a toady at power’s foot, replied. They spoke of napalming thousands of civilians as if they were discussing how many fire trucks they wanted in the Christmas parade. The comparison isn’t flippant when you remember the Christmas bombings of Hanoi in 1972, killing over 1,600 civilians.

The disconnect was the glue that spined Kissinger’s books and public pronouncements, and that won him so many admirers who like the simplicity and unaccountability of war by joystick.

Exactly 40 years ago, in November 1983, ABC aired the movie “The Day After,” about a nuclear war unleashed by the United States and the Soviet Union. It’s still one of the most disturbing and depressing movies ever made. Afterward Ted Koppel hosted a 70-minute panel discussion with seven guests, of course all of them white men. Carl Sagan pointed out that “the reality is much worse than what has been portrayed in this movie,” and described the effects of nuclear winter.

I remember to this day Kissinger’s angry and dismissive response: “I think that this film presents a very simple-minded notion of the nuclear problem,” he said, before removing himself from the implications of a nuclear holocaust and plugging some book he’d written 30 years earlier to explain why he objected to the film. “To engage in an orgy of demonstrating how terrible the casualties of a nuclear war are, and translating it into pictures from statistics that have been known for three decades, and then to have Mr. Sagan say it’s even worse than this… I would say: what are we to do about this?”

Certainly not show the consequences of the mutually assured destruction policy Kissinger in his illustrious diplomatic career made love to, like Major Kong yee-hawing over Russia. That would be simple-minded.

Maybe there’s something nice we could say about Kissinger. He helped bring the 1994 World Cup to the United States, and did it again in 2009. That’s nice. He wouldn’t be the first war criminal to love football. And like Assad the butcher, he had a sense of humor, though when he tried to get tickets to Saturday Night Live, Al Franken, then a writer at the show, grabbed the phone and yelled: “You know, if it hadn’t been for the Christmas bombing in Cambodia, you could’ve had your fucking tickets!” (I notice today Franken, whose geography had been off a bit, tweeted a tamer version than the one he gave Tom Shales in the 2002 oral history of the show.)

This man’s death, way overdue–Kissinger lives to be 100 but Hank Williams, born the same year, dies at 30?–is a tragedy only in one sense: despite the copious and undisputed record about one of the most brutal men of the 20th century, Kissinger is still garnering bootlicking tributes. The tragedy is that America does not learn. It rinses the blood and repeats.

“What more solitary death than for the one who disappears shackled in his lies and crimes,” it would have been good to say, as Camus did, a bit wishfully, as if justice really speaks in the end. But it doesn’t. Kissinger dies glorified by an empire in his image. The empire may not be far behind.

![]()

Pierre Tristam is FlaglerLive’s editor. A version of this piece airs on WNZF.