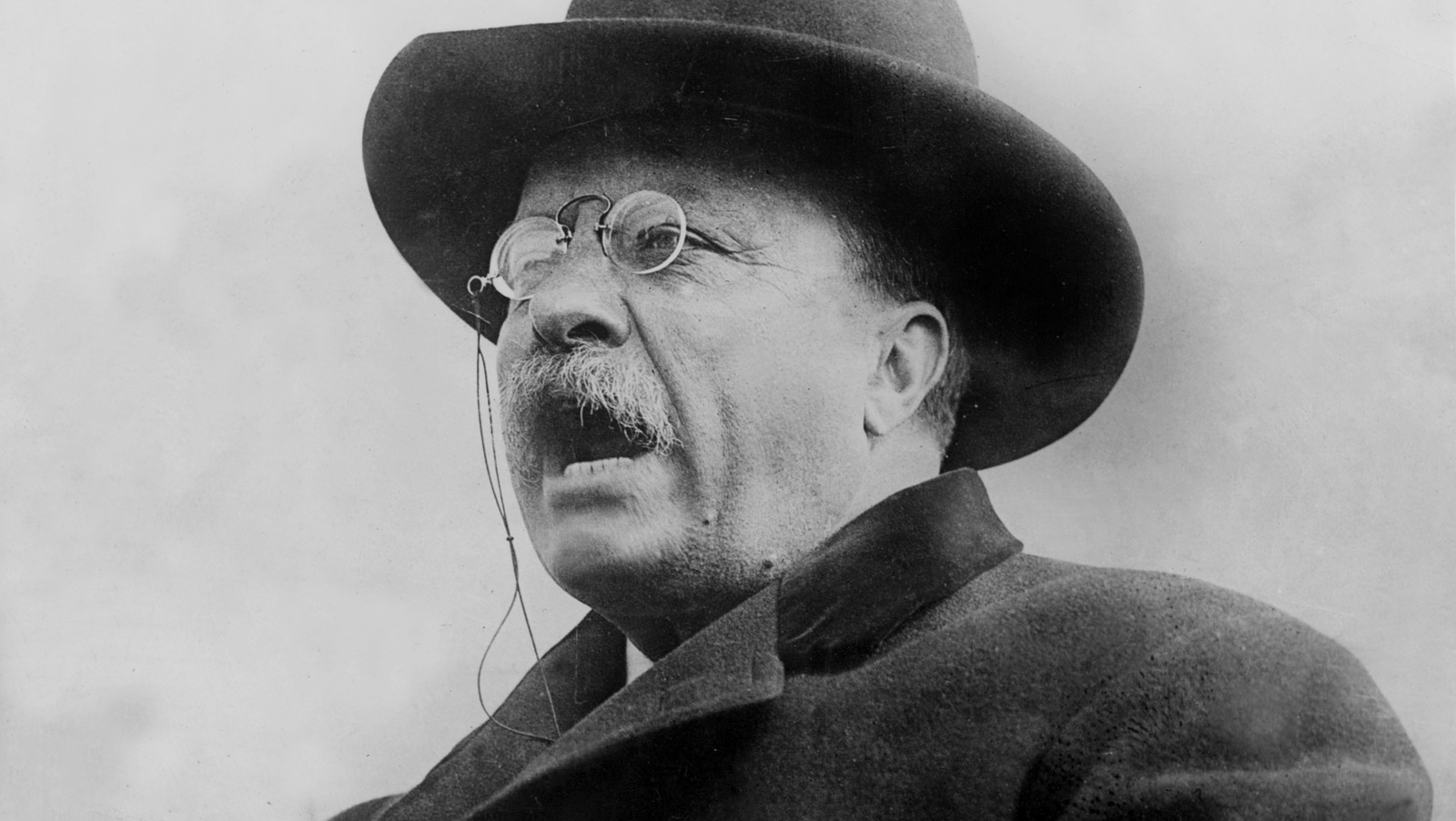

Tired, ill, and heartbroken though he was by 1919, Theodore Roosevelt wasn’t done fighting yet. Almost as soon as he pledged not to run for a third term as president in 1904, he had second thoughts. Even after the election of 1912, in which Roosevelt split the Republican Party and ran second to Woodrow Wilson, he wasn’t willing to give up on dreams of taking back the White House. His frequent attacks on the Wilson administration ran past the point of sense — the two of them shared a progressive view of government and an interest in constitutional reform. But the two men loathed each other, and Wilson was happy to deny Roosevelt the chance to become more involved in World War I.

Roosevelt remained a harsh critic throughout the war. Privately, he was acidic about Wilson as a man; publicly, he railed against the administration and such policies as the Fourteen Points. His frequent attacks have been credited with helping the Republican Party retake Congress in the 1918 midterms. They also helped him reconcile with the conservative wing of the Republican Party. Roosevelt had no intention of softening his progressive ideals, but he was happy to have consolidated support ahead of the next election.

That election was scheduled for 1920, and Roosevelt was considered the frontrunner for the Republican nomination. He gave speeches endorsing a range of progressive reforms and wrote to a friend that he wished “to make the Republican Party the Party of sane, constructive radicalism, just as it was under Lincoln” (per Nathan Miller’s “Theodore Roosevelt”). He was working on party messaging when he died.