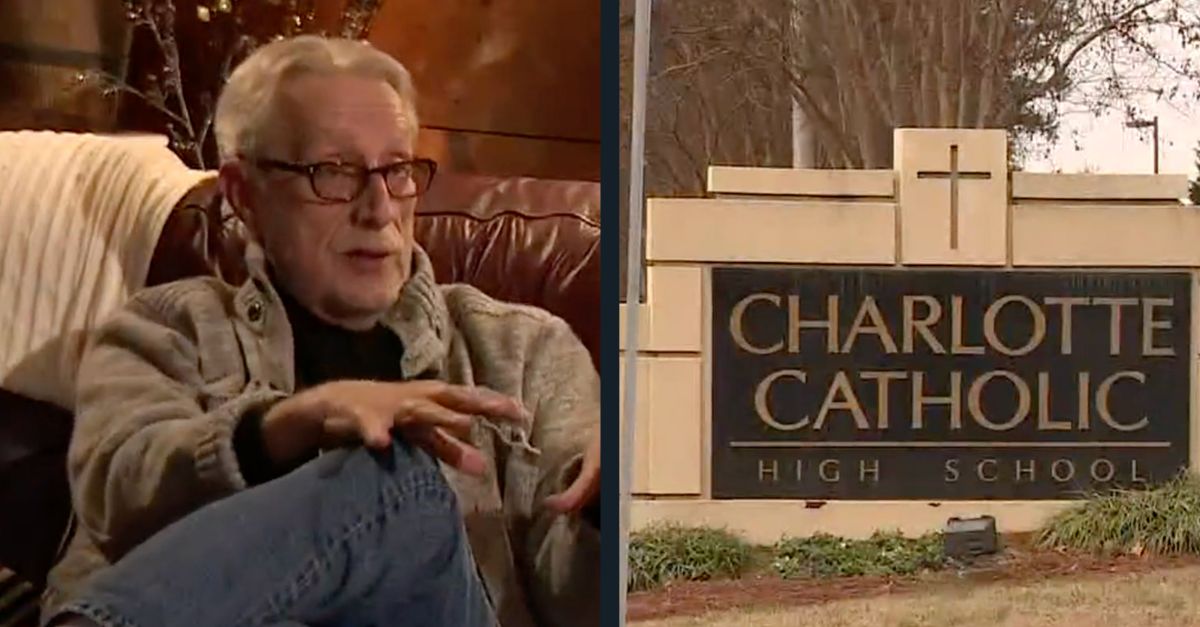

Left: Teacher Lonnie Billard discusses being fired from his teaching job because he posted about his plans to get married. Right: A sign for Charlotte Catholic High School in Charlotte, NC is shown. (Screengrabs via WCNC).

A federal appeals court revoked a gay drama teacher’s legal victory Wednesday when it ruled that a Catholic high school is entitled to fire him for marrying his boyfriend.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled that recent Supreme Court precedent allowed Charlotte Catholic High School (CCHS) in Charlotte, North Carolina, to discriminate against teacher Lonnie Billard, because teachers fall within an exception to federal anti-discrimination law.

‘Teacher of the Year’ fired after saying he would marry

Billard was a longtime English and drama teacher at CCHS and he sued the school for sex discrimination under Title VII after he was fired for his plans to marry his same-sex partner.

The district court granted Billard’s motion for summary judgment in 2021, but the Fourth Circuit reversed and ruled that as a drama teacher, Billard “played a vital role as a messenger of CCHS’s faith,” and that therefore, his employment falls under the ministerial exception to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

CCHS operates as part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charlotte in North Carolina. Although the school offers both secular and religious curriculum, religion is infused into many aspects of daily life at the school. According to the court’s findings, the school’s teaching staff plays “a critical role” in pursuing its religious mission. Teachers are expected to begin each class with a short prayer, to accompany students to and supervise their attendance at mass, and to teach their students in a manner “agreeable with Catholic thought.” It also evaluates its teachers on the “catholicity” of their classroom environment.

CCHS does not require all its employees to be Catholic, but does require its employees to conform to Catholic teachings and prohibits them from engaging in or advocating conduct that conflicts with tenets of Catholicism — including a requirement that the employees reject same-sex marriage.

Billard has worked at CCHS since 2001 after he began as a substitute teacher. During that time, Billard taught drama and English and occasionally substituted for religion teachers. The panel noted that, “Billard appears to have been an excellent and beloved teacher,” and mentioned that he won multiple awards over the years including the Charlotte Catholic Teacher of the Year award.

Billard had no responsibility to teach religion directly, and instead, referred any questions about religion to religious authorities just as the school preferred.

In 2014, shortly after North Carolina legalized same-sex marriage, Billard posted on Facebook that he planned to marry his longtime partner. CCHS learned of the post and opted to terminate Billard’s employment.

Billard sued for sex discrimination under Title VII. CCHS did not contest that it discriminated against Billard, but rather, argued that it had the right to discriminate under the “ministerial exception” to Title VII.

A ‘potent’ exception dubs teachers ‘ministers’

Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that firing someone for being gay is illegal under Title VII, a relatively new exception to that rule — which one Supreme Court justice has denounced as being an “extraordinarily potent” method of “giv[ing] an employer free rein to discriminate because of race, sex, pregnancy, age, disability, or other traits protected by law” — allows religious schools the latitude to discriminate without legal consequences.

The “ministerial exception” grew from a 2012 Supreme Court ruling that churches have full freedom to decide who will hold a position as a religious leader. In 2020, the justices expanded the ministerial exception to say that teachers also count as “ministers” for purposes of anti-discrimination law. The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg called the application of the exception to teachers “staggering” and warned that it could lead to disastrous consequences for educators.

A partially divided court

The panel of the Fourth Circuit included U.S. Circuit Judges Paul Niemeyer, a George H.W. Bush appointee, Robert Bruce King, a Bill Clinton appointee, and Pamela Harris, a Barack Obama appointee. The three unanimously supported the decision to overturn Billard’s district court win, but were split 2-1 in their reasoning.

Harris wrote for the panel and defended the ministerial exception as a mechanism that does not simply protect the church, but rather, “also confines the state and its civil courts to their proper roles.” The judge also clarified that the panel’s ruling against Billard was tied directly to mandates handed down by the Supreme Court.

Harris looked to the high court’s recent rulings involving teachers at religious schools and concluded that CCHS “entrusted Billard with ‘vital religious duties,’ making him a ‘messenger’ of its faith and placing him within the ministerial exception.” Harris acknowledged that Billard was not a religion teacher per se, but said that, “Even as a teacher of English and drama, Billard’s duties included conforming his instruction to Christian thought and providing a classroom environment consistent with Catholicism.”

“Billard may have been teaching Romeo and Juliet, but he was doing so after consultation with religious teachers to ensure that he was teaching through a faith-based lens,” Harris wrote.

Harris qualified that not all employees of a religious school would fall within the ministerial exception.

“But as the Supreme Court instructs, teachers are different,” Harris said.

In a partial dissent, King said he agreed with the ruling, but would not have decided the case under the ministerial exception. Rather, King said, the case should have been decided under a more general exemption in Title VII applicable to religious employers. King said that the panel’s majority wrongly abandoned the doctrine of constitutional avoidance by invoking the ministerial exception when the case could have been decided otherwise.

During oral arguments in September, the issue of whether an employer can waive the ministerial exception unexpectedly came up as an issue before the panel. CCHS had initially represented to the district court that it had waived the ministerial exception, and the Fourth Circuit questioned the parties at arguments as to whether waiver of the exception is even possible. Ultimately, the panel ruled that even if there had been or could be a waiver, “we ought to forgive it here” — thus leaving the ministerial exception available to defend CCHS’ sex-based discrimination.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]