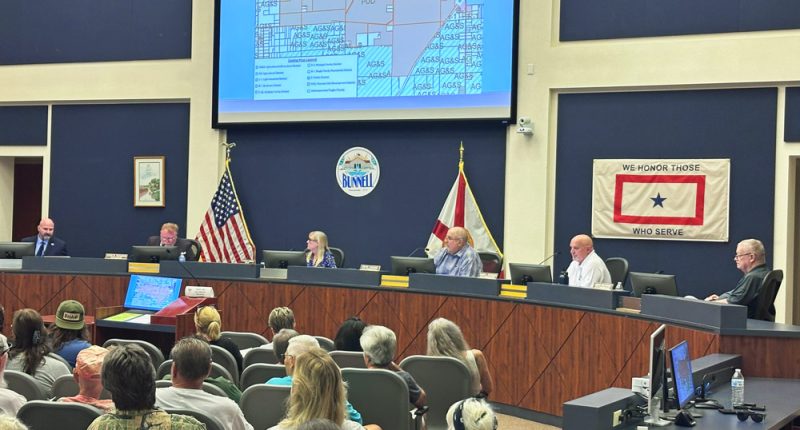

The Bunnell City Commission in a 4-1 vote on Monday rejected the planned Reserve at Haw Creek, a stunning defeat for a proposed 2,787-acre, 8,000-home development and 800-site RV park that would have increased Bunnell’s population sixfold and in the words of a commissioner, “forever change the face of the city of Bunnell” and Flagler County.

The Reserve–a name as disingenuous as its representative’s recurring claim that it was “everything you as a city asked for to grow orderly in a controlled manner,” or that it would shower the city in dollars–would have been the largest single development in the county since ITT planned Palm Coast in the 1960s.

Mayor Catherine Robinson, clearly pivoting so as not to be on the wrong side of a municipal history she has done so much to shape in the last quarter century–a history she had celebrated only two days before–joined the 4-1 majority after initially voting to approve the development, when it appeared that the Reserve had the votes: Commissioner Pete Young had initially seconded Dean Sechrist’s motion to approve. But Young switched positions after two hours of discussion and public comment.

Robinson explained neither her initial support for the development nor her opportune switch.

‘We know. We know.’

A chamber nearly full of residents with nary a Reserve supporter erupted in applause when Commissioners John Rogers and David Atkinson set down their markers in opposition near the beginning of the discussion in fierce language that suggested disbelief that the proposal had gotten that far.

“Let me be clear, this is too much for Bunnell. At 8,000 homes, we are looking at a surge in population that will overwhelm our roadways. [State Road] 11, Highway 100 and U.S. 1,” Rogers said. “If you drive them in the morning now or in the evening, you already know. We don’t need a traffic study. We know! You put that many cars at 8,000 homes, 20,000 cars, two trips a day: We know. We know. So I’m not opposed to growth. But this is too much. This is way too much, and I believe you guys agree.”

The crowd applauded again when the votes killed the proposal, to City Manager Alvin Jackson’s dismay. Jackson had been the development’s cheerleader, at no point crafting the sort of cautionary conditions or regulations that might make the proposal more palatable to the commission and more accountable to the city, or that might buffer the commission from increasing criticism from the public.

Jackson became the developer’s advocate, leaving commissioners to fend for themselves.

After the developer unveiled the proposal to the commission as a 6,000-home development in May 2024, Jackson quietly allowed an increase of density to 8,000, an allowance the commission had not ratified by the time it reached the planning board. Last December Jackson recommended that the developer be allowed to increase density at green space’s expense by 10 percent. The commission, facing down public outrage that Jackson should have anticipated, rejected the request. On Monday, again misreading a political landscape he should have been scouting rather than dismissing, he was recommending that the commission reject its own planning board’s recommendation to lower the number of homes to 5,500 and stick with the 8,000.

That approach had been Rogers’s compromise proposal: lower the total to 3,500 or 4,000 homes, a proposal Atkinson would have supported and that would have carried the day.

Traffic ‘enormity’

The “enormity” of the Haw Creek project was brought home to Atkinson after he closely studied 122 pages of traffic-impact analyses not just on surrounding roads, but on the county as a whole, and after he realized that the developer had no plans to widen the impacted roads. “Based on the study and full build out of the Haw Creek project, traffic will swell from an existing count of 8,817 daily trips to a staggering 81,943 daily trips,” Atkinson said.

Citing the city’s vision statement’s focus on quality of life, Atkinson said: “I do not believe the criteria as stated in our vision statement have been met for the Hawk Creek development. And personally, speaking with many concerned citizens of Bunnell, I have heard the voices of those who are vehemently opposed to this planned development, and I plan on acting accordingly.”

Atkinson joining Rogers in opposition to Haw Creek was not without its own subtext: new Bunnell was joining old Bunnell in preventing an unrecognizable Bunnell.

Rogers is a resident of the older part of the city’s core. Atkinson (like Sechrist) is a resident of Grand Reserve, the relatively new 700-home subdivision full of new residents that may have presaged an easier path for Haw Creek. But a development more than 10 times the size of Grand Reserve–which has not proved to be the tax-revenue windfall it had been sold as to the city–was too much even for the new Grand Reserve resident.

Atkinson was elected, along with Sechrist, last March, taking the place of Tonya Gordon and Tina-Marie Schultz. Both Gord and Schultz were almost sure-bet supporters of the Haw Creek plan, and had the vote taken place during their tenure, it is almost certain it would have carried. Both Atkinson and Sechrist campaigned–and were elected–on a platform of serious doubt about Haw Creek.

Sechrist acknowledged as much, saying how he’d been “concerned about the funding infrastructure and traffic, mainly traffic.” But since his election, he said, “nearly all of my concerns have been answered by numerous meetings with the city department heads and the developer.” The project is the work of Northeast Florida Developers, represented by Chad Grim. Sechrist took at face value the claims that the development would provide over $90.5 million in infrastructure to the city, what he compared to “a $90.5 million loan and no interest,” though it’s long been established that development is a burden, not a windfall, to local governments.

Developer’s claims

He was echoing Grim’s statements to the commission that made it sound as if the developer was doing the city a favor: “Again, no cost to you, but then you get all the revenues. We get none of the revenues,” Grim told the commission, as if blind-spotting the millions of dollars the developer reaps from selling houses. “We have to build it, and then you get the income. That’s where those numbers come from. That’s a pretty sweet deal for a city when it comes to infrastructure and the off-site improvements. The development agreement is specifically written, $0 to be spent by the city for any of the infrastructure and improvements.” (Grim said the development would not necessarily total 8,000 homes, saying “the site will tell us” how many homes there would be.)

Grim was making it sound as if that’s unusual. It isn’t. It is the standard requirement of all local developers building subdivisions: roads, infrastructure, stormwater are their responsibility.

“Yes, you will have to hire staff. Yes, you will have to maintain the sewer plants, the water plants down the road,” Grim said. “But you can have millions of dollars coming in to pay a few $100,000 worth of salaries.” It was a shocking misrepresentation: the city’s costs in added staff, added police, added firefighters, fire trucks, police cars and operational costs manyfold more than its current budget supports would be in the tens of millions of dollars.

The public comments were invariably brutal to the proposal. “The bigger picture of all of this is flooding, flooding, flooding, flooding,” Melanie Brian said. “I don’t care what St John’s Water Management says. I live there. I live right there. We had 3 feet is all I had left before that water entered my home just this last hurricane, just the last hurricane. And that is including the trees that are still there. So now you’re going to rip all that out. I’m going to have water in my house. It’s going to happen. I don’t care what they say on development. What is in black and white on a piece of paper is not what really happens.”

Comments included those from Assistant County Attorney Sean Moylan and Adam Mengel, the county’s growth management director. They both cast doubt on the proposal’s compatibility with the city’s comprehensive plan, cited flooding concerns, and suggested that they’d tried unsuccessfully to meet with city staff.

“We did feel that the overall number of units was rather high for the land, considering how wet it is,” Moylan said. Mengel told commissioners that under the parameters of a planned unit development, the city had the authority to impose limits on the number of houses–what he called “parcel-specific limiting policy,” quickly noting wryly that it was “not a term of art necessarily.”

Grim was displeased: “I heard some surprising comments from the county. And I don’t know if city staff has been in communication with the county regarding these comments,” Grim said. “But to make them at a first reading without reaching out to either the city or the developer–and again, if I’m in error, because they have reached out to the city and we weren’t contacted–but as a developer, I’m hearing the county’s comments for the first time.”

But then why did Rogers raised a document and said, “This came from the county. Here it is. This is dated June 19, 2024, where they tried to meet with staff and talk to us about this.” Was Grim never told? Did the administration not disclose the information to its own commission?

It’s now a moot point, as was the second Reserve at Haw Creek-related item on the commission’s agenda Monday evening–the development agreement, which the developer pulled from the agenda after the defeat of the proposed rezoning of the 2,787 acres.

The commission took three votes on first reading of the proposed rezoning. The first vote denied the rezoning, 3-2, based on a motion to approve. In other words, the commission denied approval. Though the vote seemed clear on its face, and would have been sufficient in most cases, the city attorney told the commission that it should vacate that vote in order to take an affirmative vote of denial–in other words, one based on a motion to deny, rather than one based on a motion to approve. The vote to vacate was unanimous. The vote to deny was 4-1, with Robinson joining the majority.

Nothing stops the developer from appealing. But that would have to be to Circuit Court.

![]()

Click On:

|