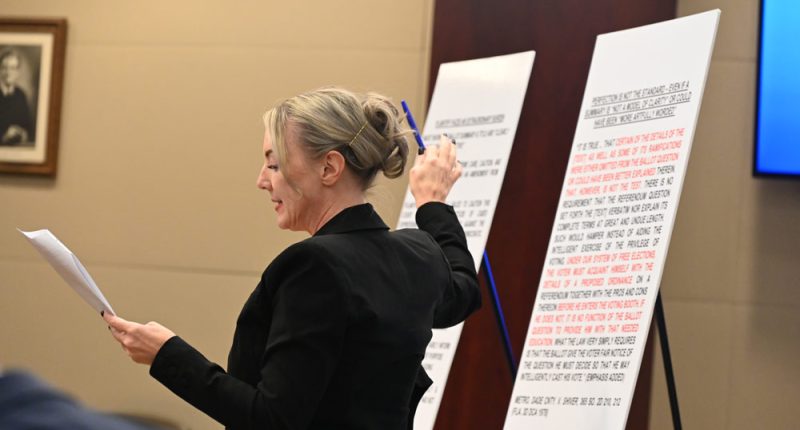

Palm Coast has mordantly and vigorously answered Mayor Mike Norris’s claim that Charles Gambaro should be booted off the council and a special election held to replace him. Attorney Rachael Crews, who represents the city, is giving Circuit Judge Chris France a buffet of arguments to find Norris’ claim “frivolous,” falsely urgent, legally groundless, injurious to the city charter, and not least, without standing.

Absent more convincing and legally grounded arguments by Norris, the judge could hang his decision on any one of those arguments singly or on all of them collectively. Of course a judge’s decisions are unpredictable. But it’s not much of an overstatement to conclude that the city’s answer, filed in Circuit Court late Thursday evening, will have Norris and his attorney on their heels.

Crews doesn’t use the word, but the style and tone of the document characterize Norris’s lawsuit with a term she may well end up using in court: absurd.

Norris, who was elected and seated in November, sued Palm Coast, Gambaro and the Supervisor of Elections on May 5, claiming that Gambaro’s appointment last fall should have ended in November, and that the council should have held an election for that seat, which Cathy Heighter had resigned in August. (The Supervisor of Elections is asking the court to be let out of the suit since that office has nothing to do with the case.)

“Tardily filed” yet claiming emergency status

Norris, represented by Mt. Dora attorney Anthony Sabatini, filed the lawsuit as an emergency action, yet apparently would not cooperate with opposing counsel to set a hearing date. France set it for July 3, implicitly rejecting the claim that it’s an emergency.

Crews, an attorney with GrayRobinson who has creatively represented Palm Coast before, called the emergency request inexplicable given Norris’s seven-month wait before he “tardily filed” it. Norris, she wrote, “did not raise a challenge following Gambaro’s appointment in October 2024, and he did not raise a challenge before (or reasonably after) the November 2024 elections.”

What Crews did not write is that Norris filed his lawsuit eight business days after Gambaro led the charge to censure Norris and send a complaint about him to the Florida Ethics Commission after an independent investigation found Norris to have demeaned, insulted and ridiculed city staff members while severely violating the charter he was now invoking in his lawsuit’s defense. (Norris also claimed he would not ever want the city to be sued three days after suing the city.)

“Even if [Norris] could challenge Gambaro’s office (he cannot),” Crews argued (the parentheses are in the pleadings), “his claim fails substantively, because there was no time to follow the City’s election process and have a legitimate election by November 2024.”

That argument was expected. Crews outlined the timeline, if with a minor blind spot. Heighter’s resignation was effective Aug. 23, while the ballots for the November election were due at the Supervisor of Elections’ office by Sept. 6, 14 days total, and 10 business days, after Heighter’s resignation, Crews writes. That left no time for the city to organize an election to fill the seat and allow candidates to gather the 165 needed petitions to avoid paying the $2,867 qualifying fee.

Crews does not mention the low number of required petitions, nor does she note that, in fact, Heighter announced her resignation in a text to Acting City Manager Lauren Johnston on Aug. 17, a Friday, 21 total days and 15 business days before the ballots were due, or that the supervisor could have pushed the due date a few days, all of which would have allowed for a larger window for candidates to run, gather the necessary petitions, and qualify.

“Gambaro has better title to the office than” does Norris, the city argues in one of its sharpest rebukes.

But she does note that Heighter’s resignation (whether from the date it became effective, on Aug. 23, or a week earlier), the deadline for candidates to submit their qualifying petitions had passed on May 13. The qualification period for that year’s election had closed on June 14. And the primary for that election was held on Aug. 20.

“By the time Heighter resigned, it was impossible to comply with the City Charter and place Seat 4 for election in November 2024,” the city argues, as the council did when it made the decision not to hold a special election for the seat, and appoint a candidate instead.

All about standing

As “insurmountable” as those obstacles were (a word Crews used to describe the impossibility of an election), the points are made moot by the strongest argument in the city’s answer: Mike Norris has no standing to sue over Gambaro’s seat.

To understand this part, it’s worth brushing up on a bit of Latin and the meaning of quo warranto, which means by what authority. Under law, Crews argues, only the attorney general or a person who may claim that he, she or they have a greater right–or is the lawful holder–to Gambaro’s seat may bring an action against him to unseat him. Norris is not that person. Norris is not the attorney general. The attorney general is not a party in the suit. Therefore Norris has no standing to sue. (Standing is especially important in these circumstances so that representative democracy doesn’t turn into a litigious free-for-all any time a result isn’t to the opposition’s liking.) Crews marshals a series of precedents drawn from half a century of Florida court cases to back up the argument.

Crews goes further, stating that “Gambaro has better title to the office than” Norris does, a biting line that makes it appear as if Gambaro has more legitimacy than Norris. But it’s not snark, and it’s not just clever wordplay, though Crews was undoubtedly smirking as she wrote it. The line is grounded by a footnote citing a rule of civil procedure that states that Norris himself–not an eventual appointee or other candidate–must have a greater right to Gambaro’s seat than Gambaro does. He demonstrably does not, making him, in fact, of lesser title to the office than Gambaro.

Norris and Sabatini may argue that this is not a quo warranto proceeding. But “Decades of Florida law make clear quo warranto proceedings are the sole and exclusive means of challenging someone’s right to hold office, and neither declaratory nor injunctive actions are permitted.” Norris is seeking both declaratory and injunctive relief from the court.

He is also arguing that France should not only declare Gambaro’s tenure illegitimate, but that a special election should be held well before 2026, when Gambaro’s term is up, to fill the seat. But that would violate the charter, goes the city’s answer. The charter makes no provisions for special elections except when the mayor’s seat is vacated. It only allows appointments–or elections at the time of general elections.

No such election is scheduled until 2026. An appointment to the seat would result in the existing status quo, Crews argues–in other words, a council majority of three votes could simply reappoint Gambaro. He has those three votes, and probably four at this point.

“Gambaro has been in office for over seven months,” the city’s answer concludes. Norris’s “delay evidences a grossly inappropriate attempt to oust a political opponent from office and bring into question months of prior votes and actions by the City Council.”

In a footnote, Crews notes the fact that Norris on his social media channels has put in question numerous council actions that carried with Gambaro’s votes, suggesting he would seek to invalidate them. The city and Gambaro “strongly disagree that Gambaro’s removal would or could call into question past Council votes and actions,” the footnote reads, with bold and italics.

Norris’s “attempt to have this Court invade the legislative sphere, remove a councilperson, and undo months of legislative actions is contrary to the separation of powers doctrine,” the answer states. Norris’s “claims are an inappropriate attempt to weaponize the judicial process against a lawfully appointed Councilmember with whom [Norris] has political disagreements.”

It was the Crews version of a mic drop.

![]()

palm-coast-answer-norris