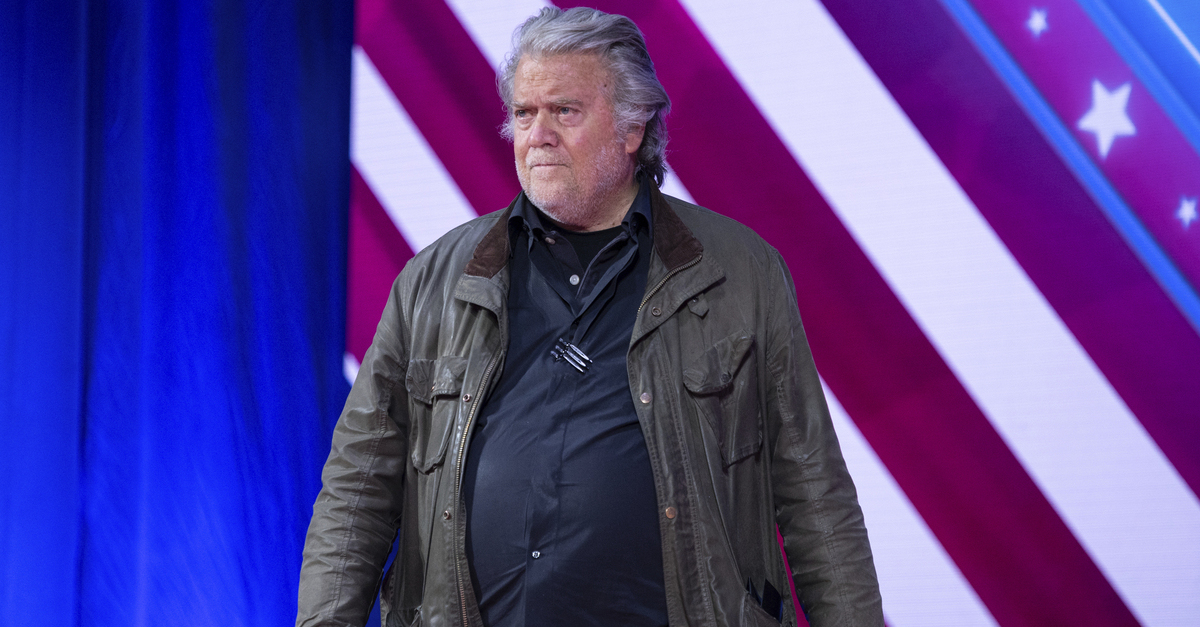

Steve Bannon, host of War Room, closes out the final day of CPAC on February 24, 2024. (Photo by Zach D Roberts/NurPhoto via AP)

Former Donald Trump White House senior strategist Steve Bannon has asked an appellate court in Washington, D.C., to keep him out of prison while he continues to appeal his contempt of Congress conviction.

In a 36-page emergency motion filed late Tuesday, Bannon asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit for a reprieve from a district court ruling last week ordering him to report to federal prison to begin serving a four-month prison sentence by July 1.

The defendant’s filing, not subtly, is replete with mentions of an intent to take his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court — pleading with the appellate court to expeditiously rule on his request so as to give him the necessary time frame to consult the nine justices.

“Bannon seeks release pending further appeal of his convictions in this case,” the motion reads. “Given his surrender date of July 1, 2024, he respectfully requests a ruling by June 18, 2024, to allow sufficient time to seek further relief from the Supreme Court if necessary.”

“Mr. Bannon intends to vigorously pursue his remaining appeals in this case and has retained experienced Supreme Court counsel,” the motion goes on at a later point. “In the meantime, he asks this Court to allow him to remain on release.”

Bannon was convicted by a jury in July 2022 on two counts of contempt of Congress, for defying a subpoena for documents and a deposition. The jury took less than three hours to deliberate. Before trial, U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols barred Bannon’s anticipated defenses at trial, largely finding them irrelevant to the charges.

The inability to mount his defense as he saw fit is what Bannon intends to raise before the nation’s high court should he get that far.

Bannon has long maintained that his defiance of the subpoenas issued by the since-defunct House Select Committee to Investigate the Jan. 6 Attack on the U.S. Capitol was on advice of counsel.

The defendant says he was instructed by his lawyer to wait for a higher court’s ruling on executive privilege issues because the information requested by the committee concerned his work as “a former executive branch official” serving under the 45th president.

“He could not inform the jury about what actually happened — i.e., that he relied in good faith on his lawyer’s advice and believed his actions were in compliance with the law — even though this allowed the government to argue with impunity to the jury that Mr. Bannon had ‘ignore[d]’ the subpoena and ‘thumb[ed] his nose’ at the Select Committee,” the Tuesday motion argues.

Notably, this line of attack essentially reprises arguments that have squarely and repeatedly found no favor in the court system so far.

But Bannon thinks the Supreme Court might be different.

In denying the defendant his preferred defense, Nichols, a Trump appointee, said he was bound by precedent that defined the term “willfully” in the contempt of Congress statute as “intentionally.”

In early May, a three-judge panel on the D.C. Court of Appeals endorsed Nichols’ understanding of the “willfully” precedent — setting the stage for prosecutors to finally request lifting the stay of Bannon’s sentence, which the lower court obliged.

The appeal of the district court’s ruling is fashioned as a motion for release pending appeal — not a stay of the lower court’s order — because of the lower legal standard required to obtain such relief.

“Mr. Bannon ‘shall’ be released if his case ‘raises a substantial question of law or fact,’ that, if successful, would result in reversal, a shorter sentence, or a new trial,” the motion argues. “Critically, this is not the same standard for obtaining a stay. Mr. Bannon is not required to show he is likely to succeed on that issue or that there has been reversible error.”

Bannon telegraphs the heart of his eventual high court appeal:

[This] interpretation of “willfully” is in significant tension with recent Supreme Court precedent and canons of construction. As the panel acknowledged, the Supreme Court has now held that the “‘general’ rule” is that “willfully” means “‘knowledge that his conduct was unlawful,’” which strongly favors Mr. Bannon. But the panel felt obliged to disregard the Supreme Court’s “‘general’ rule” because [the precedent relied on by the lower court] remained binding in this Circuit. The Supreme Court itself will have no such obstacle, however.

The motion goes on to argue that the standard does not require a defendant to argue the Supreme Court would be interested. Still, Bannon notes, the nation’s highest court has taken up “no less than nineteen cases” on the contempt statute “over the years.”

Bannon ventures some guesses as to why the Supreme Court is so interested in the meaning of the statute: “likely out of concern about its aggressive use as a political bludgeon” and “because under this Court’s caselaw, future disagreements about subpoena compliance will be met not with negotiation — but with indictments, especially when the White House changes political parties.”

Bannon’s arguments are clearly keyed toward an audience where mixing the legal and the political is the daily order of business. His motion for release pending appeal — which directly mentions the Supreme Court at least 53 times — makes that explicit.

“If Mr. Bannon is denied release, he will be forced to serve his prison sentence before the Supreme Court has a chance to consider a petition for a writ of certiorari, given the Court’s upcoming Summer recess,” the motion continues. “There is also no denying the political realities here. Mr. Bannon is a high-profile political commentator and campaign strategist. He was prosecuted by an administration whose policies are a frequent target of Mr. Bannon’s public statements. The government seeks to imprison Mr. Bannon for the four-month period leading up to the November election, when millions of Americans look to him for information on important campaign issues.”

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]