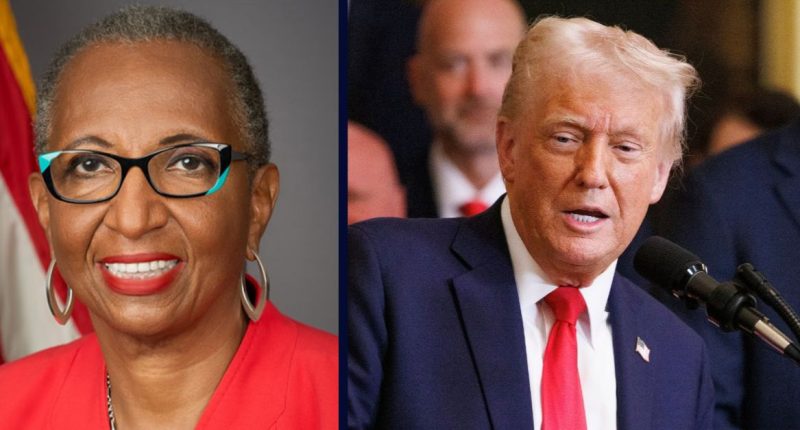

Left: Gwynne A. Wilcox (National Labor Relations Board). Right: President Donald Trump gives remarks during an event celebrating the 2024 Stanley Cup Champion the Florida Panthers in the East Room of the White House in Washington, DC on Monday, February 3, 2025 (Photo by Aaron Schwartz/Sipa USA)(Sipa via AP Images).

A member of the National Labor Relations Board who was fired by President Donald Trump late last month in a late-night email pressed her case in federal court as she tries to get her job back — rubbishing the government’s own legal arguments in a Tuesday court filing.

On Jan. 27, the 45th and 47th president read Gwynne A. Wilcox the riot act, calling her one of many “far-left” NLRB appointees “with radical records of upending long-standing labor law” who “have no place as senior appointees in the Trump Administration.”

On Feb. 5, Wilcox filed an 8-page lawsuit in federal court in Washington, D.C., calling her firing “a blatant violation of the National Labor Relations Act.”

On Feb. 10, the plaintiff moved for summary judgment. On Feb. 21, the government filed a cross-motion requesting dismissal on summary judgment. Ensuing motions practice has been fierce and voluminous.

On Tuesday, Wilcox replied to the government’s cross-motion, saying the defendants did not even bother to argue in line with the law as it stands under the current precedent in the Washington, D.C., federal system.

“The government’s argument on summary judgment leaves little for this Court to decide,” the reply begins. “The government doesn’t dispute that the President removed Ms. Wilcox without identifying any ‘neglect of duty or malfeasance in office,’ and without providing ‘notice and a hearing,’ as the National Labor Relations Act requires.”

The complaint specifically alleges Trump violated the originating statute by firing Wilcox with undue haste and for political reasons.

And political reasons, the plaintiff maintains, are absolutely nowhere to be found in the federal statute that outlines how such appointees can be removed from their jobs before their terms expire. Such firings are particularly egregious, the plaintiff adds, when the proper removal procedure is not even given a passing glance.

Wilcox argues that her interpretation of the statute has held sway in the District of Columbia Circuit for nearly 90 years under a 1935 U.S. Supreme Court case that keeps quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial multimember agencies largely insulated from the whims of the president.

In the government’s own motion, that understanding of the statute — and how courts have interpreted the statute — is not contested. Rather, the Trump administration says, the courts are wrong.

“[T]hat restriction on the removal of principal officers — officers who lead a freestanding component of the Executive Branch and exercise executive power — is inconsistent with the Constitution,” the defense motion argues. “The Constitution vests the executive power in the President alone, and requires that he be able to remove Board members at will.”

More Law&Crime coverage: Independent board thwarts Trump admin’s firing of 6 federal workers finding ‘6 agencies engaged in a prohibited personnel practice’

But the Trump administration did take issue with some case law.

The government went on to argue that a 2020 Supreme Court case limited the application of the earlier case to agencies “that exercise no executive power.” Therefore, the exception to the presidential firing prerogative does not apply to agencies like the NLRB because it “wields substantial executive power,” the government says.

Wilcox says the effort to paint the NLRB in such a light doesn’t hold water.

“The government points to the NLRB’s authority to investigate and adjudicate disputes over unfair labor practices, to order remedies in those cases, and to enforce compliance with its orders,” the reply reads. “But none of those agency powers distinguish the NLRB from [the 1935 case] or other Supreme Court decisions upholding removal protections for independent agencies.”

In a footnote, the government lawyers acknowledge that the case law — despite attempts to differentiate the facts here with the government’s “substantial executive power” argument — may not be on their side in the District of Columbia Circuit. To that end, government lawyers say, they reserve the right to argue the 1935 case “was wrongly decided.”

Wilcox points this footnote out — accusing the defendants of “essentially” ceding the point and trying to have it both ways.

The government’s overarching argument is, in fact, two-pronged: (1) agencies that exercise a great deal of executive power — as many do — cannot maintain for-cause removal rules; and (2) court decisions that conflict with this understanding — and many do, too — are unconstitutional under a separation-of-powers argument.

In other words, the Trump administration has primed itself for a wholesale restructuring of the legal landscape in terms of administrative agency officer removal. The government appears intent to take its effort all the way to the Supreme Court.

Wilcox says this perspective portends a dire future.

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

“To adopt the government’s sweeping argument in this case would thus mean invalidating for-cause removal protections for every independent agency, with potentially catastrophic consequences to the structure of the federal government,” the reply goes on.

The plaintiff is seeking both declaratory and injunctive relief. In real terms, she wants the court to announce that her firing was “nakedly illegal” and for her to be placed back in her position. The reply suggests the court should be quick in issuing a decision.

“This Court should therefore grant summary judgment to Ms. Wilcox and order both declaratory and injunctive relief,” the reply reads. “And because the NLRB is deprived of a quorum every day that Ms. Wilcox is not allowed to serve in her duly appointed position, we respectfully request that the Court do so on the same timeline as it would a motion for a preliminary injunction.”