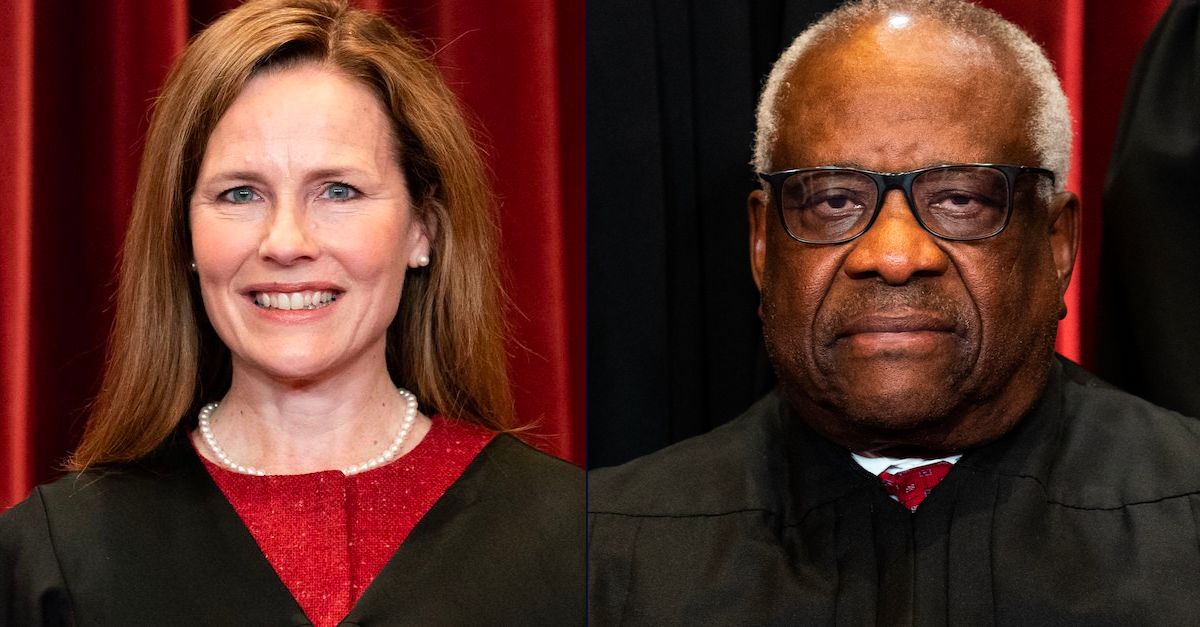

L-R: Supreme Court Justices Amy Coney Barrett, Clarence Thomas pose for a group picture of the Justices in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021 (Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images).

The Supreme Court handed down a fractured 7-2 opinion in favor of a convicted stalker Tuesday when it decided that even hundreds of “creepy” Facebook messages including one to a musician that said to “f— off permanently” are protected by the First Amendment.

Billy Raymond Counterman was convicted in Colorado after sending “true threats” via text message to musician Coles Whalen. In messages Whalen described in court documents as “weird” and “creepy,” Counterman told the singer that he had “physical sightings” of her in public and that he wanted her to die. As a result, Whalen said she suffered serious physical, psychological, and financial harm.

In his defense, Counterman argued that the statement he made via Facebook Messenger did not rise to the level of being “true threats,” and were therefore protected by the First Amendment as free speech. The trial court considered, as required by state law, whether a reasonable person would have interpreted Counterman’s messages as threats.

Counterman argued on appeal that the proper test was a subjective one that took into account whether Counterman actually intended to harm Whalen. The majority of justices agreed with him and adopted a subjective test in Tuesday’s ruling — albeit one with a relatively low standard.

Justice Elena Kagan penned the majority opinion. She wrote that in order for speech to rise to the level of a “true threat” that is unprotected by the First Amendment, a criminal defendant must have had “some subjective understanding of the threatening nature of his statements.” To satisfy that requirement, though, Kagan said a mental state of recklessness suffices. So long as prosecutors can show that a defendant consciously disregarded a substantial risk that his communications would be viewed as threatening violence, the state will not offend the Constitution.

As part of the analysis, Kagan analogized the need for threats to have a subjective component to the landmark defamation case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, which requires that a speaker act with at least “reckless disregard” for the truth or falsity of a statement to defame a public figure.

Four justices — Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, and Ketanji Brown Jackson — stood in lockstep with Kagan.

Two justices — and rather unlikely bedfellows at that — wrote in a concurrence that they were willing to accept the recklessness standard in Counterman’s case, but not in the larger swath of First Amendment cases.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, penned a lengthy concurrence , which began with a look at the purpose of deeming threats outside the realm of protected speech.

“One paradigmatic example of this would be writing and mailing a letter threatening to assassinate the President,” Sotomayor wrote. “Such laws are plainly important. There is no longstanding tradition, however, of punishing speech merely because it is unintentionally threatening.”

Read Related Also: Former Dippin' Dots CEO Accused Of Strangling Girlfriend, Who Escaped

Sotomayor raised other examples potentially deserving of First Amendment protection, such as a high school student with communication deficiencies who might be imprisoned for unwisely quoting violent music lyrics or online language or a “drunken joke” that leads to criminal prosecution.

Citing a study on rap music, Sotomayor issued a reminder that problematic disparities could result from ill-fitting legal standards.

“Unfortunately yet predictably, racial and cultural stereotypes can also influence whether speech is perceived as dangerous,” she wrote.

Despite Sotomayor’s acknowledgment that “[h]arassers can hide behind online anonymity while tormenting” both intimate partners and strangers, she and Gorsuch were unwilling to apply a subjective standard for threats more broadly.

In a solo dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas railed against New York Times v. Sullivan — again — calling it a “flawed, policy-driven” decision “masquerading as constitutional law.” Thomas called it “unfortunate” that the majority chose “not only to prominently and uncritically invoke” the case, but to even go so far as to extend its logic to a different area of First Amendment jurisprudence.

“I am far from alone,” Thomas declared, undeterred by the lack of justices signing on to the dissent. “Many Members of this Court have questioned the soundness of New York Times and its numerous extensions.” Unmentioned by Thomas: the numerous times former President Donald Trump similarly pledged to “open up” American libel laws and make it easier to sue news organizations.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett‘s dissent, joined only by Thomas, lent itself as much to Counterman’s case as it might have to the question of Donald Trump’s liability for the Jan. 6 Capitol riots.

“Incitement, as a form of ‘advocacy,’ often arises in the political arena,” wrote Barrett, who said that, “[a] specific intent requirement helps draw the line between incitement and ‘political rhetoric lying at the core of the First Amendment.””

Barrett refused to subscribe to the majority’s analogy to public figure defamation law, saying that it was not “the best analog for true threats” and provided no compelling argument for the application of a recklessness standard. Barrett slammed the majority’s conclusion as “not grounded in law, but in a Goldilocks judgment: Recklessness is not too much, not too little, but instead ‘just right.’”

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]