Flagler County government, the Hammock Community Association and Hammock Barbour, the proposed development of a 45,552 square-ft, 204-boat storage facility and 2,250-square-ft restaurant on A1A in the Hammock, are heading for another likely collision in court. A nearly-four-hour mediation session that started this morning and stretched into afternoon, involving the three parties, failed.

“Somebody is going to sue somebody out of this, that’s what I’ve gotten out of it,” the mediator said toward the end of the session.

The mediation did not start or end on anything like a conciliatory note. Milo Scott Thomas began it with a threat: he’ll file suit against Flagler County on behalf of his client if he doesn’t get satisfaction.

“I’ve never once in my life appeared before a planning board or city or county commission to ask permission for anything to do entitlement work to get approvals. That’s not where I do my work,” the Jacksonville attorney told the people around the table, who included the county’s top administrative leadership and Assistant County Attorney Sean Moylan. “I do my work in the courtroom. I am a litigator. That’s why I was hired. I was hired not to ask permission but to seek a remedy here.”

Thomas represents Bob Million. Million owns the 4.26 acres he bought in 2018 at 5658 North Oceanshore Boulevard, the former Newcastle boat-manufacturing facility next to the area’s most iconic store–Hammock Hardware. Million has already lost a lawsuit over the property, when he unsuccessfully appealed a ruling that quashed a development order at the site. He’s been looking for ways to develop the site since.

Million wants to develop the property for a commercial, recreational “marina” with 200 dry-storage boat slips and four wet storage slips for larger boats. Three buildings currently sit on the property, one of them a hulking hangar. The owner wants to replace the large hangar with the centerpiece of its development–boat storage and a restaurant.

The Hammock Community Association has not opposed the plan. Only its size. “We’ve been saying since the very beginning: Lower the number of slips, fewer parking spaces, more trees,” Dennis Bayer, the attorney representing the association, said this morning. “We could be done with this. We’ve been saying that for five years.”

For the county, it’s a different issue. Hammock Harbour may develop the property commercially. But based on the plan it submitted, it must apply for a special exception. Million applied to the county’s Technical Review Committee in July 2023 to demolish the hangar and build in its place. The county denied the application last April, concluding that the plan was not a permissible use–not without a special exception.

Hammock Harbour petitioned the county to quash that order and grant approval to the developer’s plans without going that route. It could have sued. Thomas, who laced his threats in magnanimity, said he initiated the process that requires formal mediation instead.

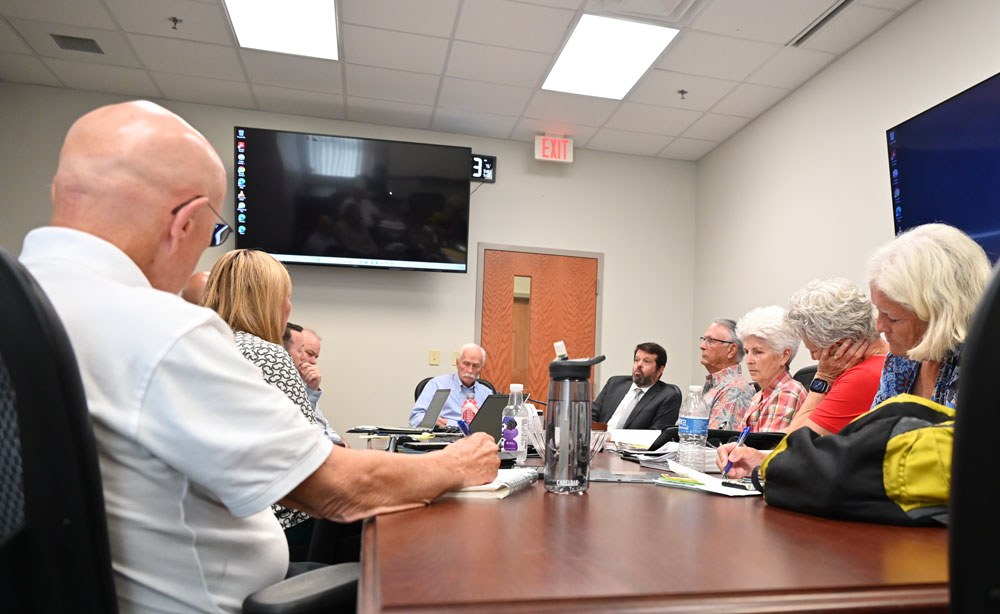

That’s what this morning’s session was all about, before Terry Schmidt, a seasoned mediator (he says he’s done over 6,000 since 1997) with a penchant for storytelling intended either as a tactic to diffuse tense situations–and there were a few this morning–or as entirely meaningless tangents.

The tension heightened the moment Thomas postured, with no indication of compromise. At least not at first. His language was not diplomatic. “We’re not going to ask again,” he told the county officials. “We’re not going to spend a lot of money to appeal things and say, ‘Gee, would you change your mind? Please change your mind on this or that. Please give us permission.’ You’ve made a decision as we sit here today and the decision is to render the property valueless. And if we can’t resolve this, we can’t come to a conclusion, we intend very much so to go do the work where I do the work, which is in the courtroom.”

There.

Except that Thomas, with Million sitting next to him, was overstating the case to the point of disingenuousness: neither the county nor the Hammock Community Association are opposed to the marina or the boat slips. They are opposed to granting a blank check without the controls afforded by the special-exception process.

What would those exceptions be? Thomas and Million weren’t interested in hearing them, because they weren’t there to deal. They consider the special exception requirement illegal. Thomas called it a “non-starter” and a “poisoned pill.”

Moylan, the assistant county attorney, said even today’s mediation was premature. Million, he said, referring to him as the applicant, “should have gone through the special exception process. If the applicant didn’t like what came out of that, there was an appeal to the county commission. And if he didn’t like what came out of that, you can appeal to the circuit court by certiorari. Or you could have alternatively invoked this procedure at that time after the appeals, after the exhaustion of your administrative remedies.”

Thomas wasn’t interested. He insisted that there was no special exception allowance the county could invoke, according to code. Bayer at that point held up a note to Dennis Clark, who heads the HCA. Bayer had scribbled: “Ignores overlay.” He was referring to the Scenic A1A Overlay District, which enables–or imposes–stricter development standards on the corridor that includes the Hammock Harbor property. That would seem to be a black and white matter of law even for the most textual of jurists.

Not to Thomas. He spoke as if the overlay was not relevant to the issue.

“That’s why I say this is a poison pill,” Thomas said. “This is not always the county’s intent. I do think it’s other people’s intent, which is if we force them down the special exception route, we have the ace in the hole to beat this.” He was clearly alluding to the Hammock Community Association. “And that’s why this is being done. We can’t be forced to apply for something that doesn’t apply. He says it’s premature. Never going to happen. We’re never going to apply for a special exception.”

That’s an untenable position for the county. “If we were to try to approve the site plan for Hammock Harbor at the staff level without processing it as a special exception, we would be sued, and we would lose,” Moylan said. Those who would sue him were sitting near him: HCA members, and Bayer. “And I would not be able to defend that action in front of the circuit court judge. The judge would look at me and say why didn’t you follow your own rules?”

That’s why the county rejected Million’s last application to the TRC. “I don’t see a way around the special exception process,” Moylan said. “Nevertheless, I do think this is a useful endeavor and not a waste of our time because we can hear each other’s points of view. In a sober discussion outside of the emotions of public hearing.” He was proposing to have each side speak candidly about what was possible. “What we can’t get past from our perspective is the requirement for the special exception process.”

And in fact, to the HCA’s distress, Moylan softened the county’s position later, suggesting that the special exception process may not be as immovable as he initially thought.

The mediation looked as if it were at an impasse. “As long as people hold those positions, I’m sort of a useless appendage to this process,” the mediator said. But he started breaking the deadlock with a simple question to Million: would he be willing to give up one parking space, for example? Million would be, as long as there was logic behind it.

That opened the way to more compromise, even from Thomas, who was now willing to hear what the county or the HCA were proposing by way of conditions. The HCA requested a break to draft a list, and 40 minutes later was ready to present it: No restaurant. No boat repairs or sales on site. No outdoor storage. A reduction of boat slips to 125. Plus some buffering measures.

“Does this pertain to any marina anywhere in the county or just you’re picking on this particular site only,” Million asked Bayer.

It pertains to any similar business in a residential area, Bayer said.

Moylan, however, said Hammock Harbor could not be prevented from building a restaurant if its parking requirements were met, and if the restaurant were not to expand beyond those requirements.

“There’s just no way to avoid that we have sort of a difference of a magnitude here that it seems somewhat unbridgeable,” Thomas said after more shuttling to a different room to discuss the proposal with Million, and–almost three hours into the season–with more diplomacy and respect than abrasive posturing. “This was originally the extra story, 240 slips, now down to 125 And no restaurant. It just renders it not economically viable.”

But it didn’t change the fact that the impasse wasn’t broken.

When Bayer asked Thomas whether his client would entertain any reduction from the 204 boat slips, Million snapped: “203.”

Bayer put away his papers and said it was pointless to go on. “I don’t know if it’s productive for us. To stay here any longer in the process,” Bayer said before leaving, along with the members of the HCA.

The next step, if Million is willing to take it–he started the mediation process, he can end it at any point–is for a more formal hearing before Schmidt on July 16 at 9 a.m. at the Government Services Building. The sides would make their case before Schmidt, who would then issue his recommendations. “It’s like carrying the mediation into the next phase,” Schmidt said.

“Under the law we have to give that mediation weight,” Moylan said. Thomas seemed willing to take that step, especially now that they see a crack in the county’s special exception wall. Million less so: “I’m reluctant to spend another $20, $30,000 bucks to to have another one of these.”

So there was significant uncertainty as to whether that formal hearing would even take place when the mediation session adjourned at close to 2 p.m.

![]()