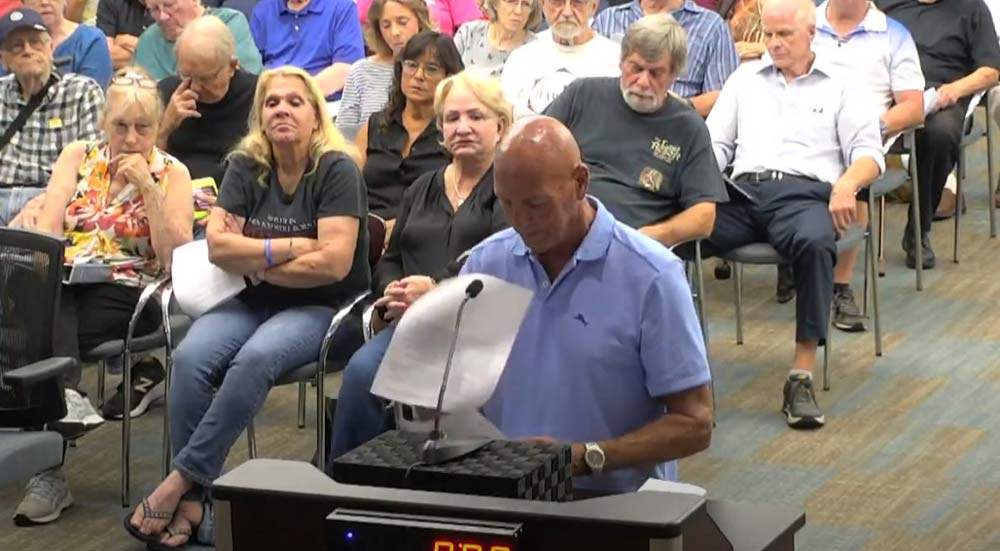

It started with the very first speaker addressing the Palm Coast City Council Tuesday evening: “I’m here to demand“–he underscored the word, pausing on it for for effect–“that the city of Palm Coast approve and fund a full and comprehensive forensic audit through an outside professional forensic auditing firm. The city has never had one performed and has fought it every time it’s been proposed. Why? If there’s nothing to hide, then our city governments should be in the sunshine.”

The speaker was Ken McDowell. Eighty minutes and two dozen speakers later, the council had consensus for doing just that.

“Based on a lot of the comments today, I would like to direct staff to look into what we need to do in order to have a forensic audit,” Council member Theresa Pontieri said. She acknowledged that annual audits are conducted, but asked for the forensic kind. Council member Ed Danko seconded.

Mayor David Alfin and Council member Nick Klufas raised issues of cost: a forensic auditor can charge between $250 and $500 an hour. But they did not object: Alfin directed the city manager to inform the council on cost and timelines before beginning to discuss parameters. Danko had sought to clarify that the audit would be “all-inclusive.”

It may not be. “It’s a long, complicated process. So before you start cherry picking, I think you should understand the entire process,” Alfin said, as the council agreed to have a workshop presentation soon about the process.

City finances are audited independently and thoroughly every year. Those audits are based on the testing of controls, sampling of transactions and financial statements, analyses of financial information and reconciliations, among other steps. (See the 2022 audit.) It isn’t in an auditing firm’s interest to be sloppy, let alone to fudge numbers or be dishonest: a firm’s reputation as much as a government’s depend on transparent audits.

A forensic audit is a far more detailed and expensive process that drills down to individual financial records. It is generally–but not always–predicated on an assumption or suspicion of wrongdoing, and backed up with at least a glimmer of evidence. “A forensic audit is used to uncover criminal behavior such as fraud or embezzlement,” an explanation of forensic audits on Investopedia states. Forensic audits are more common (and more necessary) in the private sector, where books closed to public inspection are more easily manipulated.

Public demands for a forensic audit, and council members’ surprisingly pliant surrender to one, could cast a pall on the administration in general and the financial department in particular. Yet not a single member of the council spoke in defense of either, or qualified the move toward a forensic audit at least as a placating measure for the public’s peace of mind as opposed to an aggressive investigation of city funds necessitated by probable cause.

There has been no evidence, however–no hints, no suggestions, no allegations–of financial improprieties within Palm Coast government, which has annually received commendations from independent agencies for transparency in financial reporting. What there has been, and what there continued to be on Tuesday evening, is a repeat of the same vague, general complaints about city operations–taxes, fees, spending, development–that reflect an undefined malaise that critics want addressed one way or the other. In that context, a forensic audit appears to be more of a scapegoat than a solution, and an ironically very expensive one.

to the council, the demand for a forensic audit is motivated more by general dissatisfaction with a mishmash of issues, McDowell’s opening comment was emblematic of several comments that followed. The comments were laced in vague allegations and numerous inaccuracies or outright falsehoods rather than in any basis in fact, the language overheated by innuendoes and conspiracies.

McDowell’s brief statement alone included complaints about the city being supposedly controlled by its Orlando attorneys and why the city doesn’t have its own in-house attorney when, in fact, the county’s in-house shop of attorneys, budgeted at nearly $1 million, is 42 percent more expensive than the city’s $685,000 contracted service. It included baseless charges that the city’s new garbage contract is “corrupt.” It included the false claim that the city’s utility fund is being used as a “cash cow” to fund other parts of the city budget (it is not). It included complaints about “how our tax dollars are spent,” and how “very few of those decisions benefit us taxpayers and certainly benefit real estate developers, residential and commercial,” such as rezoning decisions that have aided a boom in residential development.

Based on those misconceptions and inaccurate premises, McDowell called for city employees to “step forward” and contact the State Attorney’s Office as whistleblowers who “can remain anonymous and not have your livelihood threatened,” or contact him, “to expose the nasty underbelly of our city government.” City employees, of course–past and present–could have always stepped forward.

Equally remarkable was the council’s silence: there was no defense of the city administration, though the public comment period was followed by proclamations, one of them praising the city’s utility department.

Read Related Also: Racist shooter murdered 3 Black people, then killed himself when authorities closed in: Sheriff

Barely known or mentioned by the broader public for decades, demands for forensic audits have been surging since the end of the last century, in tandem with the surge in skepticism about government or with anti-government rhetoric. The demands for forensic audits in the context of government budgets has been closely associated with ideological rather than good-governance motives. The use of the terms in the broader culture is at an all-time high, as it was for the City Council Tuesday evening. The context and the manner of the council’s decision were as notable as the fact that a forensic audit in the city was unprecedented. None has been conducted in a local government in at least 15 years.

The city’s books are open to the public for inspection. The various accounts are occasionally misunderstood: even elected officials at times have difficulties differentiating between self-sustaining “enterprise” accounts like the city’s utility department or the stormwater fund and the mostly tax-funded general fund. The varieties of accounts and their jargon-ridden terminologies can seem arcane and impenetrable, at least at first glance. They are also easy targets for misinterpretation, with assumptions of malfeasance filling in where ledgers and fine print are too much to bother with.

“I hear of too much going on here from people that have been here for years. They’re very concerned. That’s concerning,” John Furlong said, without providing an example of something concerning.

A woman who referred to “legalized larceny” said she “can’t believe we’ve never had a formal audit,” and called for cutting “10 percent of the fat,” (without giving an example). A woman wondered how, with all the new construction, the city couldn’t generate enough revenue to afford its needs. A man wondered along the same lines how the powerful real estate market hasn’t generated needed revenue and why a 30-year utility fee would be needed to compensate for it, and yet another, reading from his laptop posed on the podium, claimed that the utility franchise fee was “likely a violation of the United States Commerce Clause” (it is not), and will face legal challenges (it has, and been ruled legal by Florida courts).

“Water bills and other bills are getting out of hand,” one commenter said, claiming–falsely–that other cities “are not charging additional fees” (water and sewer rates alone have risen 50 percent in the past decade across the country.)

Ironically, some of the speakers also demanded that the city address “the condition of our stormwater system,” just weeks after a public outcry against the city raising its stormwater rates substantially to address those very issues.

Wherever there are accusations and misinformation, Dennis McDonald is not far behind. He was there Tuesday night, opening his statement with a salvo against Mayor David Alfin: “I understand that there was a media post that was put out, okay, where you refer to a great many of us as ‘loudmouth minorities.’ And so, I’d like to thank you. I guess I’m one of those loudmouth minorities,” McDonald said, riling the crowd behind him to applause and causing Alfin to use his gavel.

“If you’re going to stand there and fabricate things that are not true, you’re going to err on the wrong side of public comment,” Alfin told McDonald. “So I give you a warning.”

This time, McDonald wasn’t wrong: he had quoted Alfin accurately from a Flagler News Weekly interview on July n31 when Alfin said: “I will always follow the hearts of all the people and not bow to any louder mouth minority of residents.” The comment, however, could have applied to any loud-mouth of any political persuasion. It was curious that McDonald so earnestly recognized himself as one.

McDonald went on to remind Alfin of the way he and the city worked “very hard to do everything they could to stymie the increase in the [impact] fees that were being charged by the educational system here in town,” the fees that help the district build new schools and that had been notoriously underpriced for years. On the other hand, the district’s enrollment has been stagnant for a decade and a half, and McDonald was inaccurate to claim that the city led the way in opposition to the higher impact fees. That was the doing of the Home Builders Association and its local echo chamber of commerce, though Alfin was by no means a fan of the higher fees. Alfin invited McDonald to a meeting with him.

There was a variety of comments that had nothing to do with any need for a forensic audit–from Josh Fabian and Nathan Phelps, the supporters of enabling backyard chickens, and several others supporting them and the initiative; from a representative of a woman speaks for the Pace Center for Girls; from a woman and a man who separately appealed to the council to “reconsider prayer at the meetings” (the council does, in fact, provide for the lengthiest moment of silence at the beginning of meetings, for prayer if those in attendance so choose, than any local government), a woman spoke in defense of a wetland, and a man who asked for a more permissive city policy about small commercial vehicles parked in residential areas.

The meeting chamber was full, however, and the overflow crowd had to be accommodated in a separate room, all drawn to City Hall on fears that the council might yet find a way to pass a new utility franchise fee, the effort that fell short again. Danko, who is running for a seat on the County Commission seat, had again rallied his troops to fill the chamber based on that fear. He was triumphant Tuesday evening, having also won a campaign talking point regarding the forensic audit. (Ken McDowell, the first speaker, socializes with Danko.)

“I think it’s clear to me at least from the public reaction to the city of Palm Coast does not want a franchise fee on their electric bill or or anything else,” Danko said. He attempted to have a motion passed that would require a referendum before a franchise fee is even considered. He didn’t get it to a vote Tuesday evening, but did manage to have an ordinance prepared to that effect for possible approval subsequently.

At the end of the meeting, when council members get a chance to speak on any items they choose, some commended each other, some commended a retiring driver-engineer in the Fire Department, some commended Fire Chief Kyle Berryhill, most commended the audience. None said a word that could dispel the pall on the city administration that the historic call for a forensic audit has created.