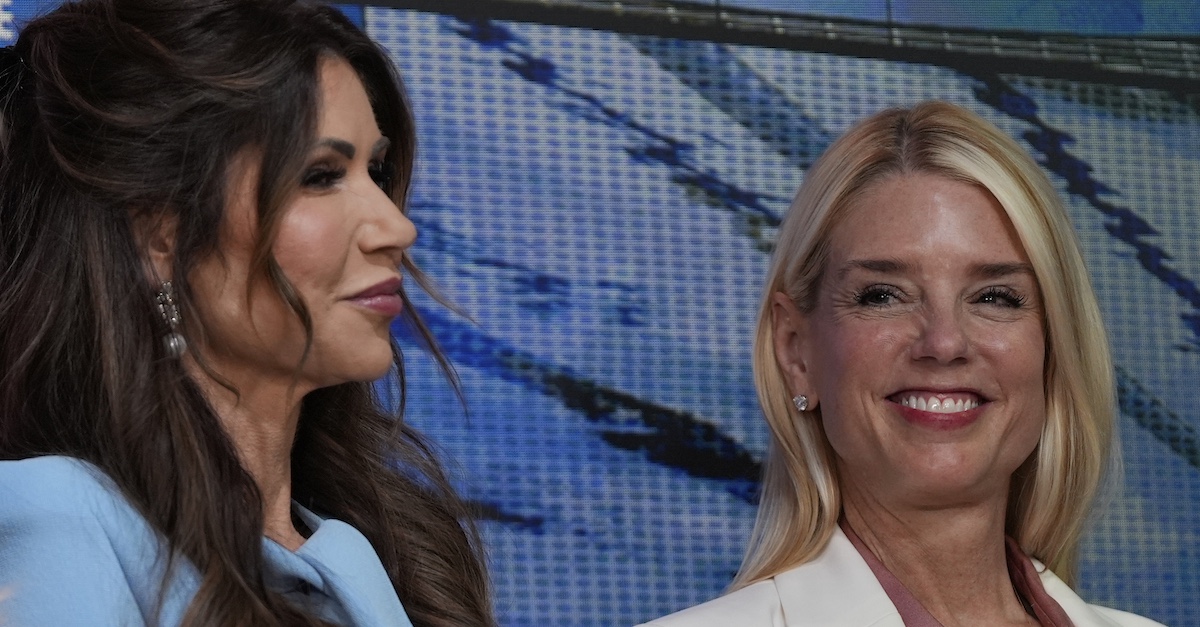

Attorney General Pam Bondi, right, and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem listen as President Donald Trump speaks before signing an executive order about the 2028 Los Angeles Olympic Games, in the South Court Auditorium of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building on the White House campus, Tuesday, Aug. 5, 2025, in Washington (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson).

As federal judges in Maryland asked one of their judicial peers to throw out the Trump administration”s lawsuit against the whole district court over “standing orders” for automatic two-day stays in cases where detainees facing deportation file habeas corpus petitions, the DOJ on Wednesday demanded a preliminary injunction to shut down the practice as an affront to the executive’s immigration enforcement prerogatives.

U.S. District Judge Thomas T. Cullen, the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Virginia before President Donald Trump appointed him to a lifetime judgeship in the same jurisdiction back in 2020, presided over a roughly two-hour hearing, where an attorney for the judges and a DOJ lawyer sparred over, what all seemed to agree, was an extraordinary lawsuit by the U.S. against a whole district court and its judges, each named in their official capacities as defendants.

Recall that, in late May, Chief Judge George Russell III said an “influx of habeas petitions” — whether those flowed from the Trump administration’s attempted Alien Enemies Act removals, which DOJ denied was the case, at least in Maryland, or from Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) deportations — led to “hurried and frustrated hearings.” That, Russell concluded, made the two-day stay a common-sense tool to manage the district court’s calendar, give judges time to confirm jurisdiction, and ensure due process in light of the U.S. Supreme Court’s rulings.

Cullen, sitting by designation in the Maryland case due to the administration’s whole-court recusal push, heard first from conservative lawyer Paul Clement, the lead attorney for the judges seeking dismissal.

“This is, to state the obvious, not an ordinary lawsuit,” and “there really is no precursor to this suit,” Clement said as he set the stage.

A former U.S. solicitor general known for his advocacy at SCOTUS, Clement called the DOJ and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s case “fundamentally problematic” from the get-go because it didn’t exhaust other available remedies to challenge the standing orders — like an ordinary interlocutory appeal to the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals or, perhaps, an extraordinary request for a writ of mandamus — before resorting to launching a lawsuit against a coequal branch of the government.

In a moment of levity, Clement apologized to the judge if he was taking up too much time, to which Cullen replied: “I’m here all day.”

Clement then asserted that the “first of its kind” lawsuit is unsupported by the various authorities DOJ cited and warned that it could mean a “litany of things” that happen in an “ordinary lawsuit” would be “fair game” were the suit to be allowed.

He mentioned discovery and depositions of federal judges as examples. Clement also raised the prospect, as he did in a brief, that the Trump administration could be emboldened to sue appellate courts over administrative stays.

“There is judicial immunity for this kind of case,” Clement said, but noted that if that is not how Cullen sees it, then this kind of lawsuit may open the door to a “nightmare scenario” of branches of government suing each other in this manner.

“All of that is avoided,” Clement said, if the government had simply appealed the standing orders or gone to the Judicial Council of the Fourth Circuit with a grievance.

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

For the DOJ, Elizabeth Hedges argued that the district court, rather than taking a breath to assess the jurisdictional landscape when the government moves to deport individuals that then seek habeas relief, engaged in rule-making authority that pretends to be an administrative stay but which instead functions as a temporary restraining order or injunction.

“This standing order appears to be unique,” Hedges said.

Cullen pressed Hedges on why the government did not proceed in an ordinary manner — appealing, seeking a stay and heading to SCOTUS if need be.

U.S. District Judge Thomas Cullen (U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Virginia).

Hedges answered that while the government is confident it would have prevailed on appeal, there were “appealability issues” it would have to deal with.

Beyond that, Hedges said the standing orders are not a “modest injunction” or administrative stay because they purport to enjoin the whole government for 48 hours in immigration enforcement matters.

It’s not a mere administrative stay, Hedges argued, but an “in personam” injunction irreparably harming the government in a way not unlike a temporary restraining order issued in a high-profile Alien Enemies Case that SCOTUS later repudiated.

The question here, the DOJ lawyer continued, is whether an injunction can be issued against the administration automatically and enjoin the government from carrying out removals simply upon an alien detainee’s filing of a habeas petition.

Cullen appeared concerned that the lawsuit was going significantly further than any theoretically similar case he’d seen.

“This is taking it up about six notches, isn’t it?” Cullen asked, emphasizing that the case caption not only names a whole district court but all of its judges by name.

“There’s nothing in the case law that says this suit can’t proceed,” Hedges answered, adding that the U.S. government “is not taking this lightly in any respect.”

Cullen wondered, however, if this kind of lawsuit would next be filed in the appellate courts or even potentially against the Supreme Court.

Hedges insisted the suit “won’t open the floodgates.”

“This is a one-off?” Cullen asked, seemingly skeptical and noting that the administration’s word on that is the only thing standing in the way.

Hedges replied that the judge “can see from case law this almost never happens.”

“This is a lawsuit to resolve differences” that are irreconcilable, not an attack on the separation of powers, the DOJ lawyer continued.

On rebuttal, Clement said the challenged standing order is not a local rule, but a “classic judicial act” for which the judges are immune from suit or an injunction. For that reason, Clement said, the case should be dismissed.

After a 15-minute break, the parties argued over the merits of the DOJ’s demand for a preliminary injunction.

Hedges claimed that the standing orders are legally invalid because the habeas petitioners, for one, didn’t request the two-day stays, which are issued automatically and without any analysis. She stated that the orders are temporary restraining orders or preliminary injunctions in effect, or even a “brand new hybrid form of relief,” unlike an appellate stay.

“Now we’re in this world where: Well, maybe it’s a stay, maybe it’s an injunction, maybe it’s a combination” — with “no historical analogue” for district courts creating a new form of “equitable relief” out of thin air, Hedges said.

Because the standing orders purport to grant class relief to persons in Maryland who are subject to removal orders, “right out of the gate, that’s a problem”; the Alien Enemies Act is not at issue in these cases, but the INA is, she said.

“These orders are invalid on their face,” hampering the government’s authority to conduct immigration enforcement, Hedges continued.

In response, Clement reiterated that the non-merits-related standing orders were within the court’s authority and gave it more time to assess its jurisdiction in a climate where habeas petitions and potential deportations had become plentiful.

He said it was “hard to see where the government’s irreparable injury is” in being delayed 48 hours.

After all, said Clement, we’ve seen the Trump administration carry out third-country deportations and defeat a federal court’s ability to prevent removals.

“With all due respect to the executive,” Clement said, “in practice it really hasn’t imposed much of an injury at all.”

Clement allowed that there might be a “small universe of cases where there could be irreparable injury,” but in those instances the government should have exhausted other means — an appeal or seeking a writ of mandamus — before ever entertaining filing a lawsuit like this one.

Clement also gamed out an absurd scenario where, if Cullen were to issue an injunction, the defendant judges could end up in contempt of their own court by not complying.

At the end of the hearing, Cullen complimented both sides for their arguments. The judge hoped to issue an opinion by Labor Day and vowed to work “expeditiously” and as “quickly” on it as he could.