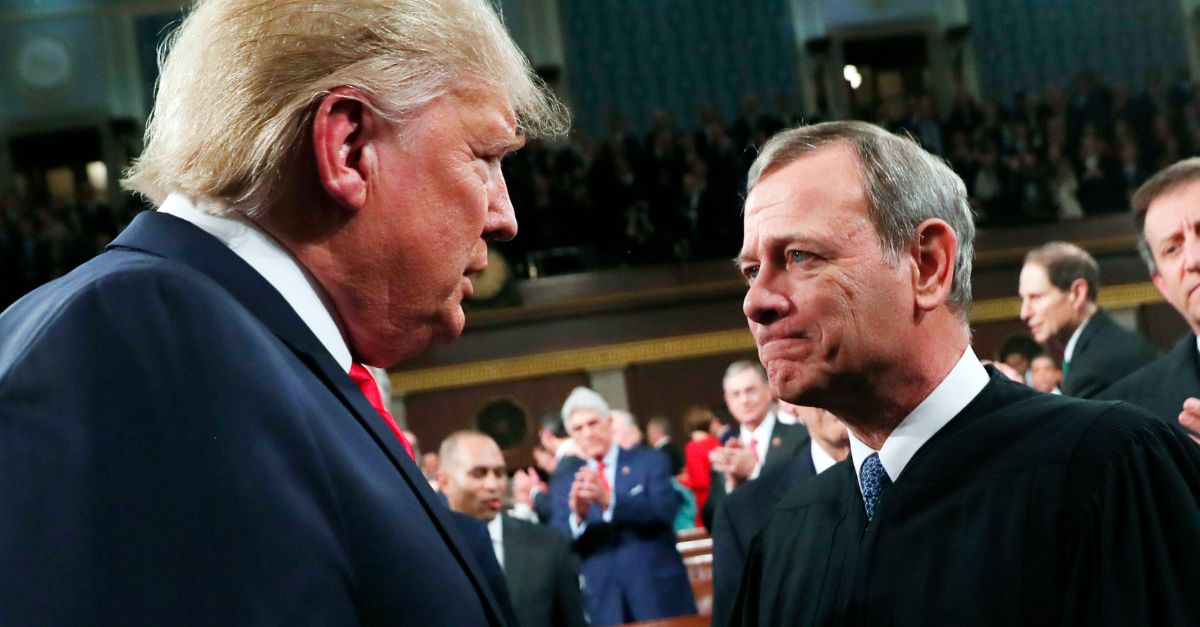

President Donald Trump greets Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts as he arrives to deliver his State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress in the House Chamber on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, Feb. 4, 2020 (Leah Millis/Pool via AP).

Chief Justice John Roberts on Wednesday once again swooped in at the eleventh hour to bail out the Trump administration, this time staying an appellate court order preventing the president from ousting two Biden-appointed members of independent federal labor agencies.

Roberts did not rule on the merits of the case, but stayed a lower court order that reinstated two chairwomen to their positions on independent federal labor boards in a case that is likely to have wide-reaching implications on Donald Trump’s continued effort to slash the government workforce and wield unprecedented control over the federal bureaucracy.

The chief justice’s order was handed down within hours of the Justice Department filing a petition urging the high court to intervene after the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., affirmed a lower court order reinstating Cathy A. Harris to the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) and Gwynne Wilcox to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

The appeals court previously reasoned that the fired chairwomen were improperly dismissed without cause, violating federal law.

Meanwhile, the administration has argued that prohibiting the president from selecting personnel in the executive branch impedes his ability to do his job, asserting, “this situation is untenable.”

“This case raises a constitutional question of profound importance: whether the President can supervise and control agency heads who exercise vast executive power on the President’s behalf, or whether Congress may insulate those agency heads from presidential control by preventing the President from removing them at will,” Solicitor General D. John Sauer wrote in the 39-page petition. “[T]he district court’s orders violate Article II on an independent and equally troubling basis. Federal courts lack any constitutional, statutory, or equitable authority to order the reinstatement of agency heads whom the President has removed and to force the President to rely on principal officers whom the President believes should not be exercising any executive power. Exercising non-existent equitable authority to saddle the President with already-removed principal officers ‘deeply wounds the President’ in his exercise of the executive power.”

Harris, a Democrat, was supposed to serve until her term expired in 2028 before she received notice in February that she had been “terminated, effective immediately.” Without Harris, the board lacks a quorum, which could hamper its ability to function as the Trump administration continues its sprawling efforts to gut the federal workforce.

Harris sued the Trump administration and won her job back through a temporary restraining order and a subsequent permanent injunction, both of which were issued by U.S. District Judge Rudolph Contreras. The administration appealed the district court’s ruling, and a three-judge appeals court panel late last month voted 2-1 in the government’s favor, staying Contreras’ injunction and allowing both firings to remain in place.

As previously reported by Law&Crime, the 2-1 ruling was particularly vulnerable to being overturned because the majority’s opinion conflicted with long-standing legal precedent stemming from the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1935 decision in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, which controls the originating statute that created the MSPB: the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 (CSRA).

In tandem, the two sources of law have, for decades, been understood to mean that a president can fire a member of an independent agency “only for inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” Harris emphatically highlighted that understanding in her en banc appeal, accusing the three-judge panel of attempting to rewrite Supreme Court precedent by allowing Trump to remove her without cause.

While the high court has indicated that it may be inclined to address Humphrey’s Executor, the en banc majority was clear that the three-judge panel had gotten ahead of itself by essentially doing away with the precedent before the justices could weigh in on the matter.

The en banc panel found that the government failed to demonstrate it suffered an “irreparable injury” by reinstating Harris and Wilcox to their board positions because the claimed “intrusion on presidential power” that the administration asserted “only exists” if Humphrey’s Executor is overturned.

“‘No such power’ to remove a predominantly adjudicatory board official ‘is given to the President directly by the Constitution,’” the appeals court wrote.

The administration pushed back on that conclusion in its Wednesday filing:

“The President should not be forced to delegate his executive power to agency heads who are demonstrably at odds with the Administration’s policy objectives for a single day—much less for the months that it would likely take for the courts to resolve this litigation,” the filing stated.

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.