Bob and Joanne Updegrave had just moved to Flagler County from Pennsylvania Republican politics in 2011, the year Charlie Ericksen decided to run for Palm Coast mayor against Jon Netts.

Lee Willman was a friend of Ericksen’s. They both volunteered for years at the Sheltering Tree, the cold-weather shelter and one of the innumerable places where Ericksen volunteered or gave of his time in one capacity or another over the years. Willman was helping him with his campaign. But she had to leave town the night of a big Tea Party event, back when the Tea Party was a thing. She asked Bob Updegrave for a favor.

“‘I want you to work with Charlie, to stick with Charlie at this event and keep him moving,’” Updegrave remembers Willman telling him. “‘Charlie needs to meet and greet as many people as he can but Charlie has a tendency to just stop and talk.’ And she said, ‘your job is to keep him moving, to cut his conversations, diplomatically, politely, as short as possible.’” Updegrave took on the job. “So Charlie was my first political job on moving here.” And he got to know him, as so many people very quickly did.

Willman and Updegrave experienced what anyone who knew Ericksen experienced soon after meeting him: the lanky Nordic and former Army instructor who’d spent a lifetime in insurance management before retiring to Palm Coast was one of the great talkers of the age. Not small talk. Not shooting the breeze. He couldn’t stand that. No: he liked to meet people, to really talk, to find out what they did, why they did it, to get interested in their work.

Before long he’d be getting involved himself, whether it was a political organization, an advisory board, a community organization or, inevitably, his own campaigns. Charlie Ericksen–he was one of those men most people referred to by both his names, his identity in full– found conversation irresistible because he found his community and all those who made it irresistible. He couldn’t stop learning about it. Campaigning didn’t come naturally to him: he found it fake and pretentious (it was one of the few things that would elicit a rare favored off-color word from him: bullshit). But he loved conversation. Conversation was his door-opener. It gave him entry anywhere, and he was everywhere: Charlie Ericksen came to like to be known as Flagler County’s Zelig, the Woody Allen character who always seemed to be in the right place at the right time.

A conservative at heart and unsentimental to his core, Ericksen was primarily a pragmatist who could speak to and get along with anyone anywhere on the political spectrum, as he did for the decade of his ubiquitous presence on Palm Coast’s and Flagler County’s political scene. He didn’t win that race against on Netts. Netts, who barely campaigned, beat him with a 13-point margin. That decisive loss might have been it for most people, though Ericksen detected that his 40 percent wasn’t that bad a showing for a newcomer running against the county’s chief statesman.

Ericksen simply picked another race, made a Mephistophelean deal with the extremist Tea Party he would soon abjure, and stunned the eminent Alen Peterson, taking the Republican primary–and the seat: there would be no general–with a 139-vote margin out of 8,000 cast. “A number that will stick in my head forever,” Updegrave said. By then Updegrave had signed on as an Ericksen campaign supporter.

It was no beginner’s luck: Ericksen would go on to win a second term after suffering a brain bleed and enduring two surgeries that sidelined during the following campaign. It didn’t stop him from handily dispatching two challengers in the 2016 primary and beating Jason DeLorenzo, the former Palm Coast City Councilman and current chief of staff in that city, with a nearly 10 percent margin.

But Charlie Ericksen wasn’t the same after that. A year before the surgeries, he’d completed a 25,000-mile bike trek, logged from years of daily biking around the city–and daily conversations with people he met along the way, from fire chiefs to city managers to homeless –that he’d started in 2008 with a new bike from PC Bike. The Man Around Town had done the equivalent of circling the globe on his bike, crushed surgeries and another election, but emerged from it all a different man: Ericksen’s decline had begun, and was unmistakable, most of all to himself.

He had memory holes that would upset him. He could no longer bike as often, and without his bike, without his conversations, he wasn’t himself anymore. On top of all that, his wife left him. The brood of dogs she left behind wasn’t enough to lift Charlie out of his funk, though his work on the County Commission and the stacks of committees and councils he served on went unabated: he still had that, and his dedication was unflinching, even if his memory occasionally was. He was saddled with cancer toward the end of his second term, but made it through that, too, along with the blitz of radiation.

He even made it through one of the vilest terms by likely the vilest man–the vilest creature–to ever serve on the County Commission, a man who insulted Ericksen to his face and threatened him off the commission, to the point that Ericksen had to seek advice from the sheriff, though he never let on: small, stupid men worried him more for the damage they inflicted on the institutions he cherished. They did not ruffle his public responsibilities.

But Ericksen knew his time was up. He did not run again in 2020. He ceded his seat, not so ironically and with some comfort and his blessing, to another paragon of civility.

Read Related Also: Riley Keough looks like a Southern belle in white dress while picking up lunch with husband after stopping by real estate office in LA

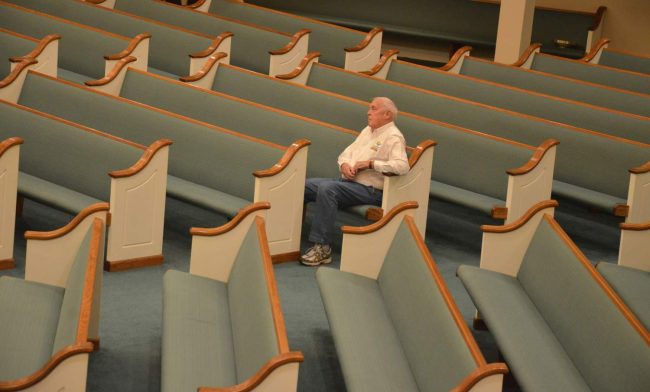

Off the commission, Ericksen’s memory lapses became more frustrating, his trademark civility a bit less guarded, his Facebook posts a bit more abrasive. The man who could always count on his fitness to carry the day was watching his own sunset and was unable to do anything about it. His public appearances diminished, with the exception of his long love for most public performances of the Flagler Youth Orchestra. He was not happy when his family removed him from Palm Coast so he could be closer to his son in Celebration. But it made sense. Charlie Ericksen was no longer the Charlie Ericksen everyone had known, the Charlie Ericksen he himself had known, the Ericksen who’d conquered Flagler.

Charlie Ericksen died this morning in Celebration. He was 80 years old.

“I loved that man. He was such a devoted, devoted public servant,” Ed Fuller, one of Ericksen’s great conversationalist and one of the people most connected to local politics, said this evening on learning the news. Fuller had driven Ericksen to many a radiation appointment in recent years. “He was such a gentleman. Great statesman, always kind, always willing to listen, and civility ruled him. That was his North Star. I’ve never heard him raise his voice at all those meetings, and he was always kind. He was one of a kind. It’s a shame we lost a great statesman in Charlie Ericksen. He was certainly the example to all who are or all who aspire to hold public office. He was certainly a sophisticated, professional and reverent man. I’m crushed. This really hurts me.”

Ericksen had been one of the 19 county commissioners George Hanns had seen come and go in his 24 years on the commission, and proof that there was not much ideology cleaving the way between Etricksen and his colleagues, even if they were Democrats, like Hanns. In fairness, Hanns’ days as a Democrat were on their death bed as he was serving a full term with Ericksen (he turned Trump in 2016, and is now a full-bore Republican, running for his old seat). But even if they hadn’t been: it wouldn’t have made a difference.

“Oh my god,” Hanns said on learning of Ericksen’s death. “Charlie was one of the three musketeers, he was one of the five musketeers, if you will, he was always level headed, good, his sense of humor was extraordinary. He was a healthy guy, he rode his bike all over the place.” Hanns recalled traveling with Ericksen all over the place, too, especially Tallahassee, to lobby or for conferences.

“He was involved in the community, almost event you’d seen him there, and I think elected officials are supposed to be seen, not every four years when they want a handout,” he said. “He was always very supportive about preserving local traditions and history and keeping up to date on all the things we’d worked with.”

County Commissioner Dave Sullivan, who announced Ericksen’s death at the beginning of a commission workshop today, described him as a “good man” who “led a good life. He served well, even under duress when he had health problems. He hung in there and finished out his term.” It was not lost on Sullivan, who’s had his own challenges this year, that he and Ericksen are the same age.

Al Hadeed, the county attorney, worked with Ericksen all eight years of his tenure. “Charlie was one who cared for all,” Hadeed said. “He was always ready to listen even to the smallest point made by a citizen. His sense of humor made people feel comfortable and opened doors for dialog. He tried to stand for the public interest.”

It is difficult to convey that sense of humor–wry, understated, never, or almost never offensive, only rarely a bit out of sync with the more politically correct times, like Charlie Ericksen himself. Whenever he spoke of his late years’ health struggles, he spoke of them as if he was a man bemused, looking at himself and wondering: what on earth?

“He never, never complained,” Fuller said. “All the issues he was going through, he just didn’t. He always pushed forward, pushed through things. He was a very optimistic fellow, and he loved this community. We’re going to suffer a great loss without him. I’d like to see something named after him.”

And not just a bike rack.

![]()