Note: This is the first of two articles on Monday’s decision by the County Commission to seek a permanent new levy for beach protection. See: “For Flagler County, New Tax to Raise $7 Million a Year to Preserve Beaches Concedes Realities of Climate Change.”

![]()

In what Flagler County Commissioner Dave Sullivan called a “dramatic change for the county,” the commission on Monday agreed unanimously to move forward with what would result in a new levy on residents and businesses to pay for $7 million in annual beach reconstruction and protection–for ever.

The county is looking to adopt a resolution as early as next month and hold public hearings for the new tax–technically called a municipal service benefit unit “fee”–in September, with enactment later this year.

It is the county’s most emphatic concession to the indisputable realities of climate change, rising seas, and storms’ increasing ravages of the county’s 18 miles of shore, eight years into the shore’s continuing state of emergency since Hurricane Matthew struck as a tropical storm in 2016, serrating the coast’s infrastructure.

It is also the county’s surrender to another unavoidable reality: to preserve the beaches, considered to be Flagler County’s greatest asset, residents across the county–not just in Flagler Beach or Beverly Beach or Marineland–will have to shoulder a share of the cost in the same way that they pay for garbage services and stormwater protection, if in different proportions.

“The goal here is when we have a problem, we can write a check,” Commissioner Greg Hansen said. “As I’ve said many times, we’re the only county in Florida that does not have a [beach] financial plan. So we need to get this done.”

But the support of Palm Coast, Flagler Beach, Bunnell, Beverly Beach and Marineland is key. Each must approved the new levy by ordinance in the next few weeks before the county

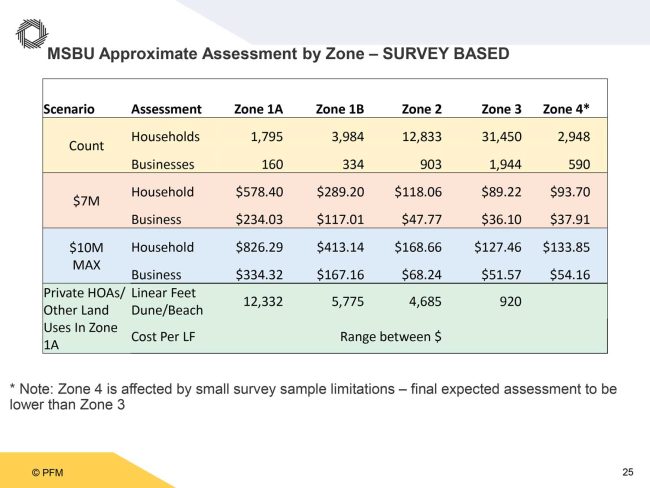

Here’s what that cost would look like, based on the county’s consultant’s preliminary estimates–keeping in mind that the actual numbers will likely look different once significant analyses are completed.

If the overall annual cost to the county were pegged at $7 million, as it currently is, the cost for households would range from $89 to $578, and $36 to $234 for businesses, depending on geography.

Beachfront households and businesses would pay the most: $578 and $234, respectively. Everyone else on the barrier island would pay $289 (households) and $117 (businesses).

The cost for households between the Intracoastal and I-95 would be $118, and for businesses, $48. For households between I-95 and either U.S. 1 or the Florida East Coast Railroad, the cost would be $89 for households and $36 for businesses.

West of U.S. 1, the cost would be $93 for households and $37 for businesses, though that latter set of figures would have numerous caveats yet to be determined. For example, the county administration currently had plans to exempt Daytona North and agricultural businesses.

In essence, the closer you are to the shore, the more you’d pay.

Alternately, if home owners’ or property owners’ associations fronting the beach were taxed at higher rates (the associations would be taxed rather than individual homes or properties), the range for everyone else would fall and range from from $25 to $550 for businesses and zero, on the west side, to $234 for businesses, assuming a $7 million annual cost.

“There’s many ways to create an assessment, infinite ways to create an assessment,” Stanley Geberer, senior managing consultant with Public Financial Management Group, whom the county hired to study how to raise money and gauge residents’ willingness to pay. PFM did so through 3,000 responses to surveys of residents by text and the web. “It has to be fair and reasonable. It has to be fairly apportioned between and among properties, and it has to demonstrate that a benefit has been received. So I think we’ve demonstrated that the benefit is received. Generally it is scaled from east to west, so that represents a fair apportionment between and among properties.”

It also has to all be approved by the cities, by ordinance, in the next few weeks.

“We do have to get consent from the cities through ordinance and this will need to happen before we can levy the amounts,” County Administrator Heidi Petito said. “We’ve got a lot of work to do. We would look to adopt this through levy in September at a public hearing.”

“If a city turns down the financing attempt, the County cannot impose the assessments within the territorial jurisdiction of that city if it is included in the assessment to be adopted,” County Attorney Al Hadeed said.

County commissioners asked a series of questions about the details: who would be exempt, who wouldn’t be, how is a $1 million beach home to be taxed similarly to a $30,000 trailer near the beach, and other details yet to be explained.

As a start, the commission was more comfortable with pegging Flagler County’s commitment to the $7 million a year than to $10 million, which was also among the options. But delaying the plan by a year could then move the overall cost closer to that $10 million.

The commission is also willing to use some of the money already generated by the tourist sales surtax to beach management to further defray that cost. That tax currently generates $1.6 million for beach management, according to this year’s budget.

That would immediately bring down the overall levies expected, to less than the lower ranges, and would start building the county’s beach management reserves–assuming no immediate storms wrecked that plan.

The county will determine if any businesses would be exempt, or whether there would be additional rates for home owners’ associations and other specialized properties, such as public buildings or state utilities. It would also have to determine how or whether to tax agricultural lands, which are exempt from fire assessments. Religious properties are also typically exempted. But one or another existing exemption doesn’t necessarily mean the residents should be exempted from the beach protection tax. “They’re still putting the garbage out on the curb on Wednesday. We still need to collect for that service,” Geberer said. Similarly, the county might want to see the beach protection tax the same way.

“The next part in my analysis is just understanding how a lot of the different communities up and down the beach are are funding this,” Commission Chair Andy Dance said. “We’ve seen examples of St. Johns County doing it, all the way up and down the East Coast, there’s different government agencies that are supporting this in order to renourish the beach.”

He noted a hurdle ahead: convincing the public that those skinny dunes the county has rebuilt on two occasions since Hurricane Matthew are meant to be temporarily protective, and are different from rebuilding entire beaches, as is now the plan. “So from a communication standpoint, we still have some of that work to do as well,” he said.

“There’s general agreement to go forward but the devil is in the details and how we’re going to establish the costs for each area,” Sullivan said.

The dollar figures were based on a survey that was itself organized by naturally-breaking zones. Zone 1 was the barrier island (with Zone 1a reflecting beachfront properties, and 1b properties that ara away from State Road A1A). Zone 2 was from the Intracoastal to I-95. Zone 3 was from I-95 to U.S. 1. Zone 4 was from U.S. 1 to the west end of the county.

“I think the numbers overall are very fair,” Hansen said. “But I think where we run into trouble is Zone 1B,” especially with the fairness aspect between wealthier and poorer properties that may end up facing the same tax, or fee.

![]()

beach-management-taxes-plan-2024