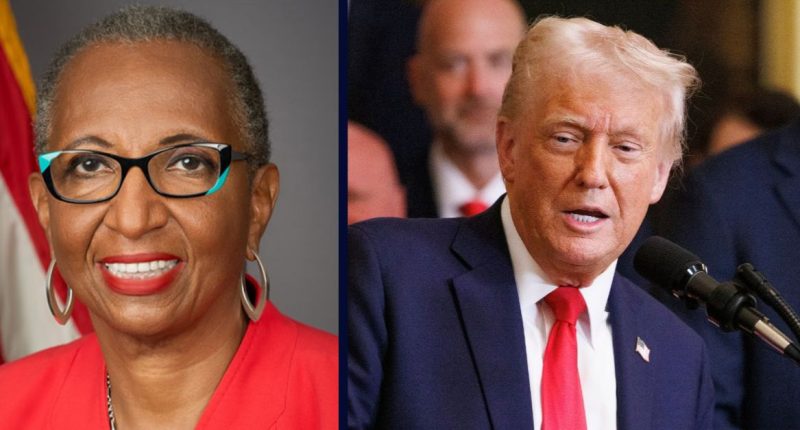

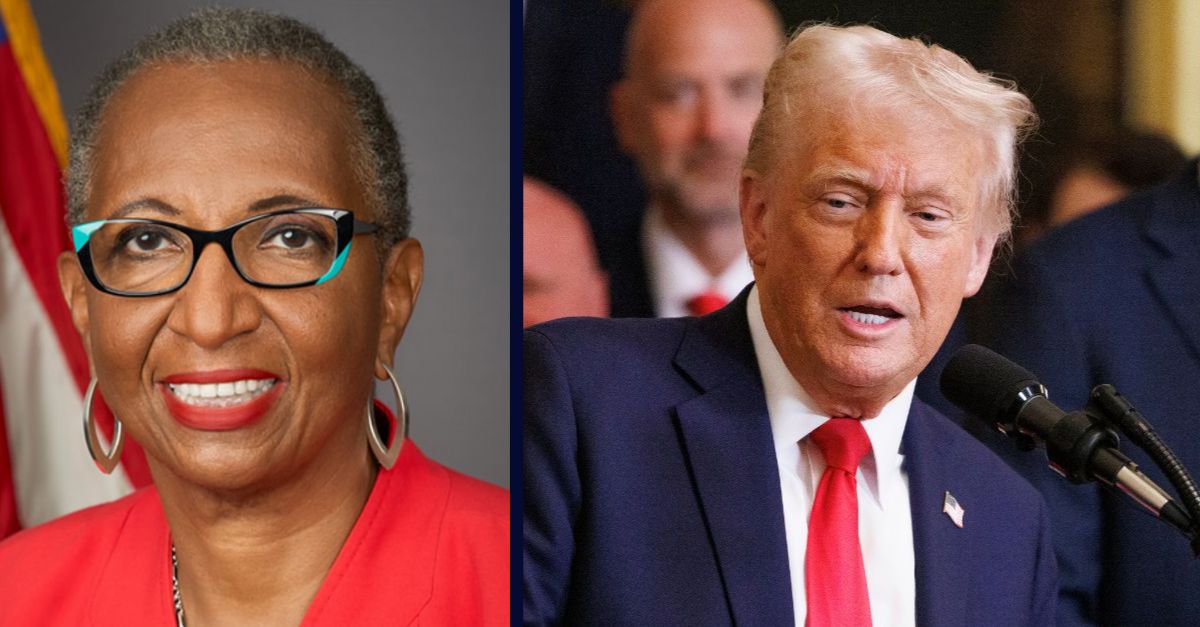

Left: Gwynne A. Wilcox (National Labor Relations Board). Right: President Donald Trump gives remarks during an event celebrating the 2024 Stanley Cup Champion the Florida Panthers in the East Room of the White House in Washington, DC on Monday, Feb. 3, 2025 (Photo by Aaron Schwartz/Sipa USA)(Sipa via AP Images).

A federal judge was clearly dismayed by arguments from the government during a Wednesday afternoon hearing over the fate of a member of the National Labor Relations Board who was fired by President Donald Trump upon his return to the White House.

U.S. District Judge Beryl A. Howell, a Barack Obama appointee, unsparingly quizzed lawyers for both sides in the dispute about whether Gwynne A. Wilcox could be reinstated on the NLRB.

But while the questions were generally piercing across the board, the judge decidedly and repeatedly expressed unease with the “unitary executive theory” being advanced by the Trump administration.

“The theory that has been pressed … is basically saying Congress doesn’t even have the power to set some conditions on the removal power at all,” Howell said at one point. “It’s up to presidential whims.”

The issue before the court is whether or not the president, by way of a late-night email sent by a subordinate, was within his rights to fire Wilcox, a Joe Biden appointee, simply because the administration views her as a “far-left” appointee who is not the right ideological fit.

Readers may recall that this very issue is currently snaking its way through several different cases in the D.C. District Court system. The administration has similarly moved to fire, on a purely political basis, members of the Merit Systems Protection Board and Office of the Special Counsel. In each instance, however, the plaintiffs have won reprieves from judges — and maintained their jobs. And, in each lawsuit, the same 1935 Supreme Court case has proven decisive.

The analysis in each of those recent vintage cases was rattled off, almost offhandedly, during Wednesday’s hearing. The judge took notice of those decisions — mentioning her courthouse colleagues by name — and suggested the rulings might provide some guidance, but would not necessarily be dispositive, making clear that her own analysis of that controlling high court case would hold the day.

The case in question, Humphrey’s Executor, stands for the idea that Congress intended to keep “quasi judicial and quasi legislative” agencies largely insulated from the whims of the president.

For the plaintiff, the upshot of that case is clear as day in the present fight. To hear Wilcox’s attorney tell it, the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the originating statute that created the NLRB, was passed two months after the Supreme Court’s 1935 opinion for a reason.

“They knew about Humphrey’s Executor and they were relying on it,” the plaintiff’s lawyer argued.

Under the terms of the NLRA, members of the NLRB can only be fired for two reasons: “neglect of duty or malfeasance in office.” These limited bases are termed “for-cause” removal protections.

The Trump administration, for their part, says they don’t have any problem with Humphrey’s Executor. Rather, the government says the for-cause removal section in the NLRA is unconstitutional.

The defendants say the old case doesn’t apply because it dealt with a broader suite of removal rules — which added “inefficiency” to the list of fireable offenses. The plaintiff says the case has long been understood to be shorthand in favor of for-cause removal protections and insists the government is trying to overturn the precedent.

The government’s attorney pushed back, arguing that the 2020 case of Seila Law v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau should control the outcome here. That case gives the president wide power over executive branch hiring-and-firing practices — with an exception “for multimember expert agencies that do not wield substantial executive power.”

Conversely, the government says the NLRB does, in fact, wield “substantial executive power,” because it makes labor rules for the whole country, which brings it under Seila Law. In turn, an agency subject to Seila Law means the president can fire members at will.

Without giving all her cards away on how she views the interplay between Humphrey’s Executor and Seila Law shaking out, the judge strongly suggested she was skeptical of the government’s position due to a more overarching reason: the unitary executive theory.

Addressing Wilcox’s lawyer, Howell framed the Trump administration’s position as the “absolute presidential power of removal.”

In agreeable fashion, the plaintiff’s attorney said, “The current executive is giving the most extreme version of that theory a spin.”

The judge pushed things a bit farther.

“It’s no longer theoretical,” she said, almost laughing. “It’s here for us, for how we’re going to be governed.”

Wilcox’s lawyer replied: “It matters for separation of powers analysis that this is the first time a president has asserted this theory,”

Howell appeared to agree.

At one point, the judge picked up an argument first advanced by the plaintiffs. The judiciary also sets precedent and judges also make rules, the judge acknowledged — by verbally gesturing to “the volumes” of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The government’s lawyer rejected the analogy.

“The president isn’t accountable for the judiciary, he’s 100% accountable for the NLRB,” the defendant’s attorney argued. “The rules of the road are fundamentally different.”

Pressed on why the president’s power to name the chair and the majority of the members on the NLRB are “not sufficient” exercises of executive power in light of congressional intent to cabin said power, the government’s lawyer said those were not enough for an executive intent on changing political dynamics at the federal level.

“Those sort of nudges don’t work,” he said.

The judge shot back with a telling question: “Is it just up to the president’s whims?”

As the hearing went on, Howell staked out her position further.

“I think it really comes to how much can Congress legislate on the removal power,” she said at one point.

The judge added that “history and practice have shown” the president can be limited by statutes passed by Congress.

“Is the position you’re advocating here, the purest absolute power of the president with respect to removal?” the judge

The government lawyer said the president’s removal power has been “the law of the land” since 1789.

“Saying the president alone has the removal power begs the question of whether that power can be checked by Congress,” the judge said.

The judge even disagreed with the notion that Wilcox would be reinstated if she ruled in her favor — characterizing the request as more like removing the roadblocks to her serving out her term.

In rebuttal, the plaintiff’s attorney argued that the government’s understanding of what it means to exercise executive power would encompass far too much. The judge signaled her agreement there.

“Every agency in the executive branch is exercising executive power,” Howell mused — calling the argument “tautological”

“That’s a broad definition,” the judge added.

Howell went on to suggest the government’s understanding would unleash a precedent-shredding state of chaos. The judge then asked Wilcox’s attorney, in a somewhat leading fashion, what kind of remedy Congress could legislate if the Supreme Court were to endorse the “unitary” theory of presidential removal.

The question was left open — but the implication was clear.