Last Friday, the Wildlife CSI Academy hosted a special learning experience involving protected animals, some which were nearly extinct, at the Georgia Safari Conservation Park in Morgan County.

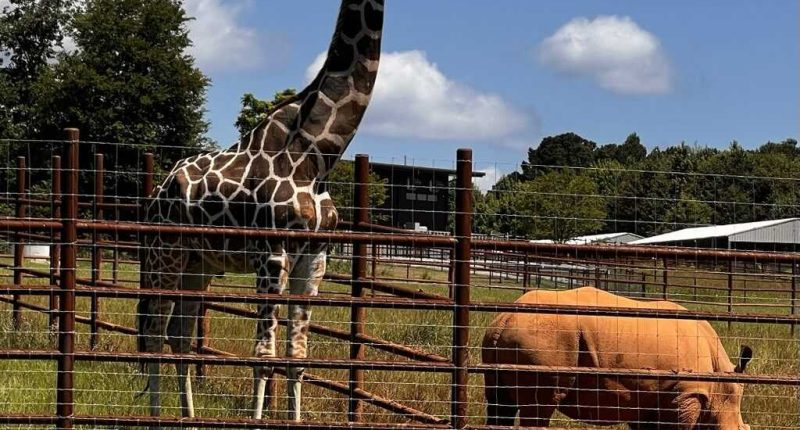

Tucked inside green, rolling hills in Madison, Georgia, the safari park is drawing attention not just for its giraffes and rhinos but for its growing role in fighting wildlife crime.

The park, which opened in 2024 and sits on over 500 acres in Morgan County, has been named one of TIME’s World’s Greatest Places for 2025. It’s home to over 40 exotic species, many of which face threats from poaching and trafficking in their native habitats, including the Asian buffalo, which were once on the edge of extinction.

Unlike a traditional zoo, the facility is structured as a working wildlife refuge. It offers sanctuary to at-risk animals and takes an active stance against illegal wildlife trade via five habitats situated on the park.

“There are only 30 to 90 addax left in the wild. Seven of them are here,” Safari guide Addalynne told McCollum’s group, who rode through the park on an open-air safari game viewing vehicle.

Veterinarians and staff trained specifically in antelope care oversee the addax at the park. The animals live in expansive, open habitats designed to mimic their natural range. The park contributes to global conservation by maintaining a breeding population that helps preserve genetic diversity, which is critical to species recovery programs.

Multiple conservation and law enforcement organizations have partnered up to help not only the addax herd, but all the animals at the park, some of which were seized from trafficking rings or displaced by habitat loss and natural disasters. Staff members are trained not only in animal care but in evidence handling, secure transport, and quarantine protocols—procedures normally reserved for federal wildlife officers.

The park uses surveillance systems and 24-hour security to deter threats, including attempted theft or harm. While no poaching attempts have occurred on site, park officials say the threat remains real—especially given the presence of endangered species like rhinos, which render high prices on the black market for their horns.

Rhino horns are often sought after for unsubstantiated medicinal value. The horns are also used for ornaments and jewelry, and sometimes as an “aphrodisiac,” although no scientific evidence exists to back up the claims, the academy’s founder, Sheryl McCollum, told CrimeOnline.

“[It’s] false belief that rhino horns possess aphrodisiac qualities or can enhance sexual performance,” she said.

As international wildlife trafficking continues to fuel extinction and organized crime, staff at Georgia Safari, along with McCollum, say they’re committed to proving that conservation and community tourism can work hand in hand.

“Wildlife trafficking and organized crime heavily affect animal populations by killing thousands of animals every year. The Wildlife CSI Academy is training street level law enforcement on how to combat these crimes. Every officer needs the tools to recognize these crimes, make initial respond, identify, document, collect and preserve evidence,” McCollum said.

“Experts say every 20 minutes an animal or plant goes extinct. We have several animals that are facing imminent extinction due to poaching. The Amur leopard, pangolins, and rhinos are among the most vulnerable. Because of poaching, my great-grandchildren will only be able to see these amazing creatures in books.”

The park aims to become a model for 21st-century conservation. By combining refuge, education, and community involvement, it shows how responsible tourism can help shield vulnerable species from exploitation.

As the park expands its reach and partnerships, it strengthens both the state and the global effort to combat poaching and wildlife crime.

To connect with McCollum and learn more about the Wildlife CSI Academy, reach out to her on Facebook or X.