By Mazarine Pingeot

Americans hold on to their “freedom of expression”, an identity marker of their history, which is distinct from French freedom of expression.

Historically, freedom of expression in the United States was coupled with freedom of the press, since it was essentially through the latter that one could express oneself publicly. The First Amendment stipulated as early as 1791:

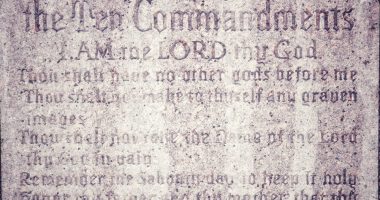

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, or to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

We understand that the initial vocation of this defense of freedom of expression was to limit the power of leaders and to protect individuals, as the liberal tradition wants, concerned with individual freedoms against any authoritarian threat coming from the State.

Freedom of expression on social networks

What is it today? Freedom of expression is once again at the center of the game and claimed, not by muzzled citizens, but by the State itself, or rather by the one who is at its head and intends to manage it like a lucrative business: Donald Trump.

Among the most fervent defenders of the First Amendment, the libertarians and the Silicon Valley billionaires who own the new public spaces called social networks, want above all to decide the rules that govern them.

For Mark Zuckerberg, freedom of expression is embodied in the lifting of moderations that AIs were responsible for and the elimination of “fact-checking”, identified as censorship or as a “woke” and right-thinking bias.

At another level, it would therefore be a question of eliminating all verticality to achieve the consummate horizontality of an ideal democracy where the State would no longer intervene at all, except to endorse this decentralization of information and this liberation of speech.

This is the meaning of the words of Vice President J.D. Vance, denouncing the rule of law and European regulations that would oppose freedom of expression at the Munich Security Conference on February 14. According to him, “democracy is based on the sacred principle that the voice of the people counts. There is no place for sanitary cordons. Either you defend this principle or you don’t.”

This speech was praised by Jordan Bardella (“France must follow the example of the USA”), Éric Ciotti (“a speech for history”), and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan. After his speech, J.D. Vance supported Alice Weidel, head of the AFD, a German far-right party that has just obtained more than 20% of the votes in the legislative elections of February 23.

Triumph of public opinion

Let’s put aside the instrumentalization of the principle of freedom of expression in the service of Trumpian propaganda and Gafam, and take seriously the defense of this principle as it is conceived across the Atlantic, that is to say without limits.

We then note a double shift: moral first, since invective, verbal violence, racism, homophobia, would not have to be banned “in the name of freedom”. We can obviously ask ourselves how being homophobic or racist is an expression of freedom of thought, and whether it is not rather a matter of impulse.

If we follow Rousseau in Du contrat social, moral freedom “alone makes man truly master of himself; for the impulse of appetite alone is slavery, and obedience to the law that one has prescribed for oneself is freedom”, we are entitled to consider the expression of hatred and resentment as that of a form of alienation, or even as the very symptom of servitude. But let us move on and bet that in a democracy, any opinion is good to say, although we may find it distressing that it is no longer backed by a minimal form of reflection.

A second shift is just as worrying: it concerns the truth. If we can say anything, that “the Earth is flat” and that “extraterrestrials are going to colonize it”, and if these “opinions” are relayed by communities excited by the originality of the non-“official” thesis, the common reality is in danger.

We have known this since the 20th century, as Hannah Arendt showed, total lies can end up replacing the truth due to a growing indifference to the difference between truth and lies. This process, which began during the two totalitarianisms of the 20th century, continued with the advent of mass democracy, up to Kellyane Conway, Trump’s former communications advisor, who put forward “alternative facts” that were neither true nor false. This process, which began during the two totalitarianisms of the 20th century, continued with the advent of mass democracy, up to Kellyane Conway, Trump’s former communications advisor, who put forward “alternative facts” that were neither true nor false to support her president’s lies during his inauguration in 2017.

It is also useful to make the link between a certain use of freedom of expression and “bullshit,” to use Harry Frankfurt’s expression. Indeed, if freedom of expression was supposed to allow the expression of opinions (including radical ones), it has not – historically – been calibrated to say anything. Saying anything should not be a right or a principle: it is at most a fact. A fact that could remain private, and one could wonder why it deserves to appear in the public square.

The fact remains that “saying anything” can have real effects, or rather the destruction of reality. Thus, the historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet revealed the functioning of negationism in Un Eichmann de papier, asserting that negationism (in this case that of Robert Faurisson denying the existence of the gas chambers) is based on the transformation of the truth of fact into opinion.

This is not without echoes with the consequences of freedom of expression without framework and without limits. Insult is authorized, but, even more, “anything goes,” “alternative fact,” falsehood—everything that tends to blur the lines between truth and opinion.

France and freedom of expression

France has taken this “pathology” of freedom of expression seriously, by regulating it on several occasions, as already provided for in Article 11 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen: “Every citizen may speak, write, and print freely, subject to being held responsible for the abuse of this freedom in cases determined by law.”

However, the law has evolved: first, the law of 29 July 1881 on freedom of the press imposed a legal framework on all publications, while providing that “printing and bookselling are free”. We must then understand that restrictions are also the conditions of possibility of this freedom, because by protecting respect for the person, minors, or even the invasion of privacy, they give substance to what we mean by freedom.

More recently, the Pleven law of July 1, 1972 sought to combat racism in France, supplemented by the Gayssot law in 1990, which made Holocaust denial a crime. The Taubira law extended the crime to the non-recognition of trafficking and slavery as crimes against humanity in 2001.

Of course, these laws have sparked controversy, particularly from historians who considered that their freedom of research had been undermined and that politics had no place intervening. Debates that therefore pitted those in favor of stricter supervision of freedom of expression, including legal proceedings, against others who rejected it but in the name of research. We are still far from the outcry across the Atlantic.

In the past, the State or the Church censored for reasons of either public security (in other words, to curb political opinions that could shake the foundations of power) or morality. Today, freedom of expression, won through hard struggle against these two bodies, consecrates insults and verbal violence, but also the possibility of claiming the freedom to say anything.

Continuing to speak of freedom of expression to designate post-truth produces an intellectual confusion that is particularly difficult – and yet essential – to untangle.

Translated from the French by Google Translate.

![]()

Mazarine Pingeot is a philosophy professor at Sciences Po Bordeaux.

![]()